I’ve been on the road for 36 hours now, and I’m pretty much on the other side of the world from where I started back in rain drenched England. At last, I’m approaching the final legs of the journey—just a short one-hour flight to go.

Things have gone smoothly so far, I’m thinking, as I wander up to the check-in desk for the last leg of my trip. “The flights full,” the attendant tells me, “You’ll have to wait until tomorrow.

Contributed by

Following a mixture of smooth talking and plain old pleading, I managed to “unoffload” myself, and I’m soon in the air heading for New Britain Island, Papua New Guinea. I should be out for the count, but I’m too excited to sleep. Ever since I first learned of this country, from the pages of David Doubilet’s, Light in the Sea, I’ve wanted to come here. I guess I’m a slow starter, for I read that book nearly 20 years ago!

“Make sure you get a window seat!” was the message from everyone who I knew who’d been here. The view really is staggering. Papua New Guinea is as raw and untamed land as you’ll find. The landscape ranges from mountainous highlands to rich rainforest; its ecosystem attracts scientists from the world over, and upwards of 850 languages are spoken here. With such extraordinary variety, how apt that the country’s motto is, “Unity in Diversity”.

In no time, we touch down at Hoskins airport, and from here, it’s just a one-hour drive, through endless neatly ordered rows of oil palm, to my destination—Walindi Plantation Resort on the shores of Kimbe Bay. Characterised by a friendly atmosphere nurtured by the owners, Max and Cecilie Benjamin, this has long been the secret haunt of some of the world’s best underwater photographers .

Diving

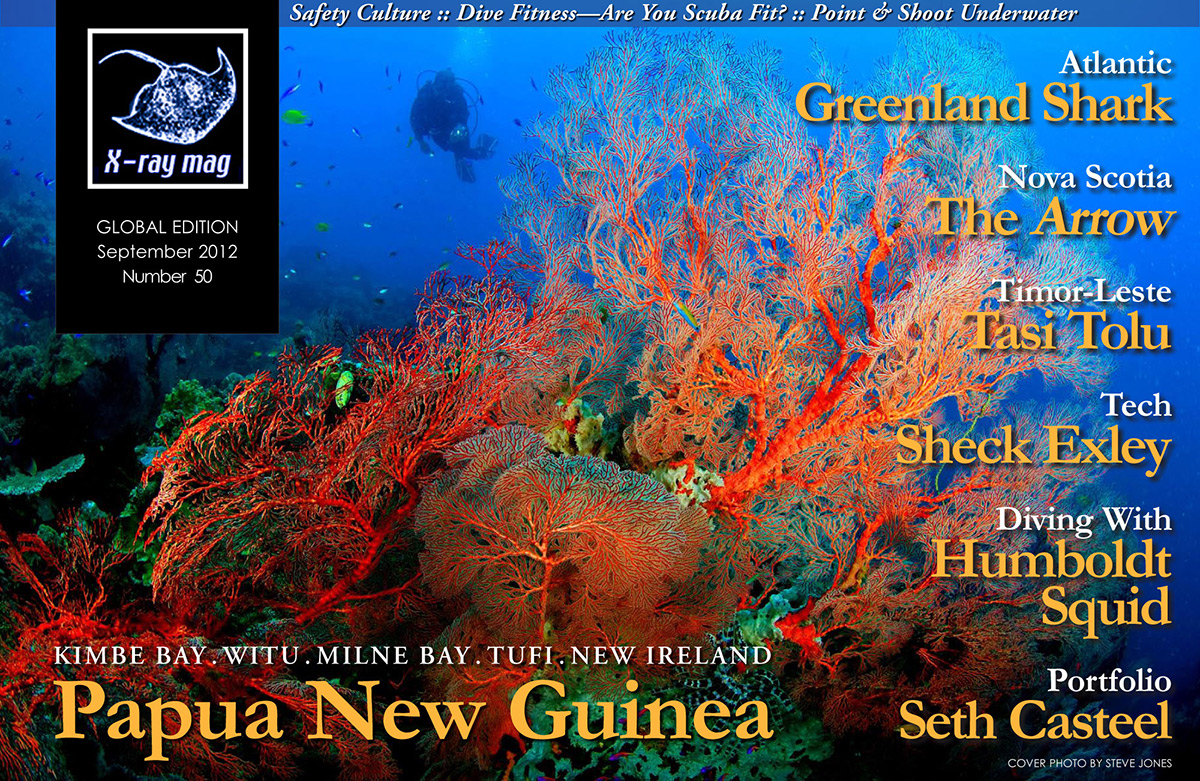

The next morning, I’m heading out to South Emma Reef. Descending into the crystal clear water, the first thing that strikes me is the sheer size of the corals and sponges here. Encircled by tall volcanic mountains, Kimbe Bay’s reefs are protected from the fiercest storms, while the mooring buoys in turn keep the reefs protected from anchors. This has enabled corals to grow undamaged to gargantuan sizes. My descent is checked only by a school of barracuda. Over the next days, it becomes apparent that just about every reef seems to have their own school!

Following Max over the drop off, we soon find a swim through filled with life; the walls are a mass of colour. Emerging through the other side to the upstream side of the reef, the scene is stunning—a wall of fusiliers are being hunted by tuna and huge barrel sponges protrude from the reef wall. The myriad of corals provide shelter for longnose hawkfish, scribbled leatherjacket and fire dartfish—just a few examples of the 900 plus species of fish that have been recorded in the bay. This reef already ranks amongst the best I’ve ever seen—and it’s only the first dive!

The beautiful underwater formations can be attributed to the large numbers of reef building corals; there are at least 440 species present. Whilst we are moored on the picturesque Restorf Island, we are, however, reminded of the bird life that has made Papua New Guinea as important for ornithologists as it is for marine biologists. The screech of sea eagles orbiting overhead emphasises the prehistoric feel of this place, whilst underwater, we find a reef adorned with giant elephant’s ear sponges.

Reefs like this in places such as the Red Sea or the Maldives would be crowded with dive boats, yet here we are totally alone. I feel like I am discovering a place that has been untouched and unexplored— a sensation that I rarely experience anymore. As I dive these waters, I am filled with the same enthusiasm and excitement that I used to experience in my youth. I am once again discovering the unsurpassable beauty that the underwater world holds.

Max operates three day boats from Walindi and just a few safari boats dive these waters—that’s it! There are dozens of reefs to dive, and yet, not another boat in sight.

The Witu Islands

Venturing beyond the shelter of the bay requires one of these safari boats, and the FeBrina has become a firm favourite amongst serious divers all over the world. She’s captained by Alan Raabe, one of the industry’s more flamboyant characters, whose personality is as colourful as the T-shirts he wears. This diving-focussed ship has both the safety and the enjoyment of the divers foremost on the agenda.

Diversity is everywhere in Papua New Guinea. Not just in the marine life but in the type of diving itself. On my first morning in the Witu’s, I awaken moored inside a sheltered volcano crater within Garove Island. From the stunning reefs of Kimbe Bay, I am now in muck diving territory—this is the domain of the critters.

The black volcanic mud of the crater is home to countless numbers of the weird and wonderful—ribbon eels, mandarin fish and various species of mantis shrimp.

My guide, Digger, has a passion for these creatures, and his ability to find anything I suggested was remarkable.

I have long yearned to observe and photograph the rare tiger shrimp, and with Digger’s help, I succeeded in doing so. I was able to watch two of them move across the coral—a sight that I thought I would never be able to see. Already, Papua New Guinea has enabled me to turn some hopes and dreams into reality.

Returning to the FeBrina, I am greeted by the beaming smiles of children rowing towards me in their canoes—a particularly enchanting experience. Upon their arrival, our respective modes of transport became trading posts. In exchange for the fresh fruit the group held out to us, we gave pencils, paper and other simple yet desired trinkets. As we followed them back towards land, the haunting songs of local tribesmen greeted us as they practiced for an upcoming festival.

In the thick of the action

The Witu Islands are not just about muck diving—in fact far from it. The offshore reefs build on the tempo of the diving from that experienced in Kimbe Bay—and that is no small feat. From stunning seascapes like the The Arches and the wonderful gorgonians of Barneys’s Reef, the frenzy of marine activity increases in a crescendo, finally reaching its peak at Lama Shoals, or Krakafat, as it’s more affectionately known .

A dive at this site makes the senses roar, for in the thick of the action huge schools of jacks and barracuda orbit overhead, and batfish hover in the current before vast bushes of black coral. Grey reef sharks can be seen cruising back and forth, whilst fairy basslets perform a dance of death with the preying jacks, who work like a pack to bay their quarry. Whilst my mind spins from all this I am given a window of tranquillity, as a turtle effortlessly glides down and settles on the reef.

Spectacular formations

After the pristine, coral rich reefs of Kimbe Bay, the Witu Islands had offered big fish school action at its best, tempered with superb critter diving. This is really what makes the diving here so special—it’s the variety.

The Father’s Reefs don’t buck the trend of offering something different. This reef group lies some 70 miles northeast from Kimbe town and are dominated by spectacular underwater formations and vast expanses of hard coral. Midway reef in particular has a reef top that is covered with stag horn coral as far as the eye can see, while Fathers Arch is a beautiful grotto filled with countless soft corals and gorgonians.

Encounters with big animals are common in these waters—hammerheads and even orca have been seen in the region. Sadly, I did not witness them, however, three stunning silvertip sharks graced my entire dive on Shaggy’s Ridge, whilst at least 15 white tip sharks accompanied me while diving Belinda’s Reef.

It seemed that as the names of the dive sites became more obscene, so the diving got better and better. So I had high expectations for Killibob’s Knob. Alan’s sense of humour knew few boundaries when he was thinking of names for the sites!

A gathering place for an impressive number of grey reef sharks, it soon became clear that it was not actually the sharks that rule this reef at all, for the animal that stole the show was a great barracuda. At nearly two metres long, his boldness was in no doubt, after he sent a pair of juvenile greys packing, this barracuda claiming the fish scraps thrown in by the kitchen staff as his own. There is only room for one boss on this reef!

Conservation through education

As I stand on the jetty of Walindi on my last night, I am joined by Pascal Waka. “I really worry about the state of the world,” he says. “The ice caps are melting. The oceans are being fished out... Where will it all end?” His subsequent observations on the human race’s troublesome tenancy of ruining this planet belie his young 25 years of age. Pascal works at Mahonia Na Dari, a marine institute dedicated to protecting Papua New Guinea’s reefs through education and research.

Opened in 1996, following a co-operative effort between the Nature Conservancy, the European Union and Walindi Plantation, its name means “Guardians of the Sea” in the local Bokove language. It has provided courses for thousands of school children all over the country, as well as being an important research station for marine scientists worldwide. While industrialised nations lay waste to the oceans, a glimmer of hope lies here in a country that prides itself on uniting diversity, rather than exploiting it.

A time capsule

During my last hours in Papua New Guinea, I reflect on all that it has shown me. The stunning seascapes, the variation in the dives, the big fish action along with the critters make this whole region a truly special place. A land that is caught in a time capsule, just like the World War II Japanese Mitsubishi Zero fighter plane laying silently on the sea bed in Kimbe Bay, which we’d explored a few days earlier.

The area is a reminder of what coral reefs really can be if protected from humankind’s overbearing influence. It’s wonderful to see such healthy populations of sharks when they have all but disappeared from many other areas, succumbing to the obscene demand for shark fin soup. As I depart this land, I can’t help wondering how much time the sharks of Killibob’s have left? ■

The author wishes to thank the team at Walindi Resort and MV FeBrina liveaboard for their help in creating this article. Steve Jones is an underwater photographer and journalist in the United Kingdom. See: www.millionfish.com