The appearance on the radar of a new world-class area for scuba diving is a rare and extremely welcome event. It is even better news when it is a place as steeped in history and culture as this one.

Contributed by

Factfile

Simon Pridmore is the author of the international bestsellers Scuba Confidential: An Insider's Guide to Becoming a Better Diver, Scuba Professional: Insights into Sport Diver Training & Operations and Scuba Fundamental: Start Diving the Right Way.

He is also the co-author of Diving & Snorkeling Guide to Bali and Diving & Snorkeling Guide to Raja Ampat & Northeast Indonesia, and a new adventure travelogue called Under the Flight Path.

His recently published books include Scuba Exceptional: Become the Best Diver You Can Be, Scuba Physiological: Think You Know All About Scuba Medicine? Think Again! and Dining with Divers: Tales from the Kitchen Table.

For more information, see his website at: SimonPridmore.com.

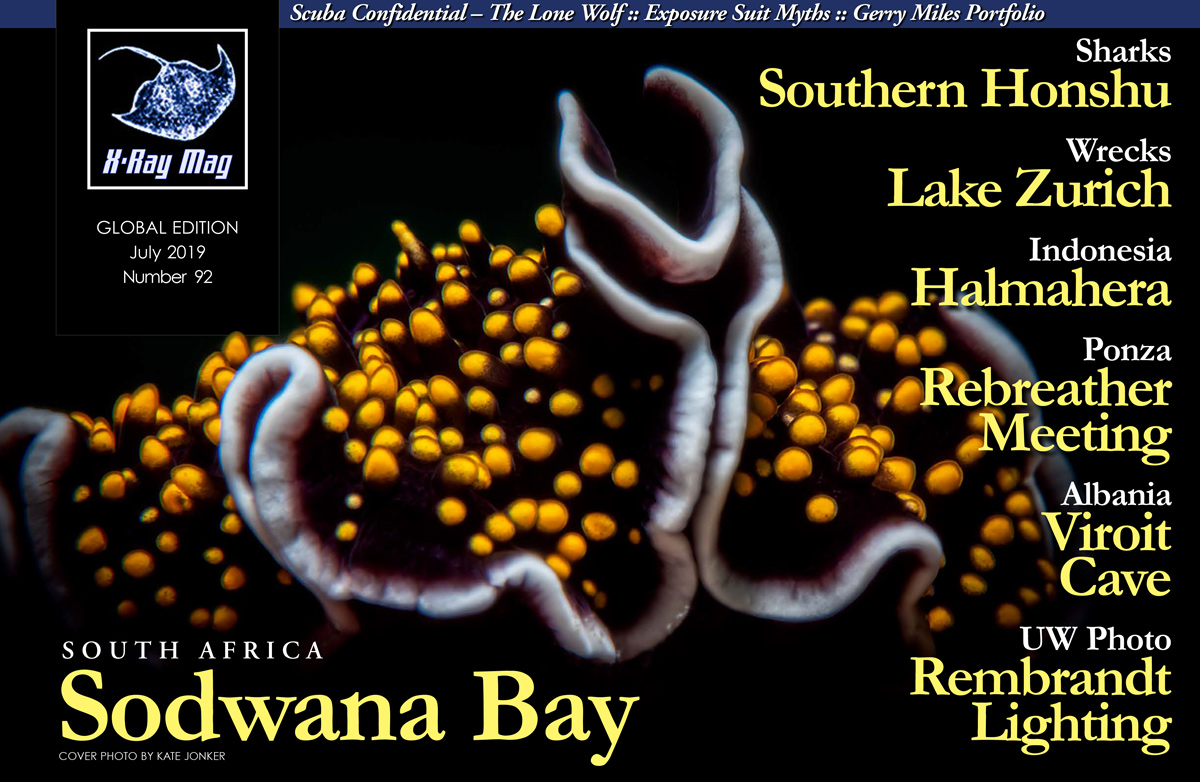

This new dive destination is a collection of rocks and islets in the northeastern region of the vast Indonesian archipelago, on the edge of the Pacific Ocean. They lie southwest of Halmahera, a large, heavily forested, sparsely populated island, sculpted by volcanic forces into the shape of a letter “K.” To the north of Halmahera lie the Southern Philippines, to the northwest lurks similarly spidery Sulawesi, and to the southeast lie the islands and mountains of West Papua. These waters are at the heart of the Coral Triangle—the planetary epicentre of species diversity.

How is it, you might ask, that divers have only started visiting these islands comparatively recently? Just look at the map. They are situated between Lembeh, Bunaken and Manado Bay on one side and Dampier Straits and the rest of Raja Ampat on the other side. Of course, the diving is going to be spectacular!

A combination of factors seems to have been involved. First, the islands are remote and there is little tourist infrastructure, even now. (This is definitely NOT Bali.) Second, liveaboards tend to focus on the two jewels in Indonesia’s diving crown, Komodo and Raja Ampat, plus a couple of destinations in-between, which they visit on transition cruises. Southwestern Halmahera requires a detour from these routes. Third, somehow, nobody in the diving world thought to follow up on a 2005 survey of the area carried out by American-born Australian ichthyologist Gerry Allen, PhD, during which he recorded a phenomenal 803 species of fish in 37 hours of diving at 28 locations. (If anyone did follow it up, they managed to miss all the good places, or they kept quiet about it.)

This is part of the Indonesian province of North Maluku, which is likely to be a new name to you. However, it has not always had such a low international profile. Hundreds of years ago, these islands were highly sought after by spies, explorers and entrepreneurs from Western Europe, who were desperate to find the source of cloves, nutmeg and mace.

These enormously valuable and rare spices, sold at huge profits by Chinese and Arab traders, were fabled to emanate from mysterious dots of land on the edge of the known world. The nations of Western Europe expended huge effort to find the source of the spices, in order to cut out the traders and take the profits for themselves. Christopher Columbus was one of these explorers and it was his quest to find a western route to the “Spice Islands” that subsequently led to his bumping into the Americas.

Now, the same islands are being sought after for very different reasons: lots of fish, sharks, spectacular underwater scenery and superb coral reefs—in short, world-class diving.

The isles of cloves

Our gateway to Southwestern Halmahera was the island of Ternate, dominated by the flattened cone of the active Gamalama volcano. Ternate and its similarly shaped (though more cone-like) neighbour Tidore were at one time the only place in the world where clove trees grew.

The two islands were ruled by sultans whose clove monopoly made them extremely rich, although they spent most of the money they made on armies to fight one another. Their power and wealth, however, did not last long, following the arrival of representatives from the major Western European naval powers.

Once the Europeans discovered where the cloves came from, their superior marine and weapons technology gave them control of the supply. The first to arrive were the Portuguese, closely followed by the Spanish, the Dutch and the British. Then, they spent the next couple of centuries fighting each other over the precious spices, until roots and seeds were smuggled away to be planted on tropical islands elsewhere and the islands were no longer special.

This period in history is visible today in the clove, nutmeg and cinnamon trees that dominate the forested lowlands of Ternate and Tidore and in the various ruined forts of various nationalities dotted around the coast. We spent the first two days of our trip getting over the jetlag and doing a little sight-seeing, learning about the history, savouring the spicy fragrance of the forests, visiting the world’s oldest clove tree and watching people harvest and dry the crops in the sun. We even stopped and bought some spices to take home. The cloves made our bags smell wonderful!

The other evolutionary

Ternate’s second major claim to historical fame is that it was, for a time, the home of Alfred Russel Wallace. Wallace was living on Ternate when, in 1858, he sent to Charles Darwin his seminal paper on evolution, entitled “On the Tendency of Varieties to Depart Indefinitely From the Original Type.” This was even referred to as the Ternate essay, and in its nine pages, it describes the theory of evolution by natural selection.

On receiving this paper, Darwin immediately decided to publish his own work on evolution, and arranged for the Ternate Essay and two of his own papers to be read to the Linnean Society of London on 1 July 1858. The world would never be the same from that day onwards.

We visited the house Wallace lived in when he was in Ternate, but it is a little underwhelming. There is nothing in the way of a museum there, just a small bungalow with a caretaker, indicative of the low level of tourist infrastructure in the region.

We stayed in Ternate at Vila Marasai, run by a gentleman named Pak Hasrun, who used to work as a tour guide. He has established an excellent homestay comprising 11 air-conditioned rooms with ensuite bathroom (although some rooms have no hot water) in a large two-storey house just out of the city and above the university. Vila Marasai seemed to offer a much more attractive option to the grey concrete-block business hotels in the centre of town. Pak Hasrun can serve meals and arrange reasonably priced tours.

Out to sea

So, while we found the big islands of Ternate and Tidore fascinating, fun and fragrant, we had really come all this way to dive. On our fourth morning, we bid farewell to Pak Hasrun and took a taxi to the dock in front of an enormous mosque to join the Tambora liveaboard for a ten-day cruise around the islands to the south and west.

The Tambora is a phinisi, a wooden ship built on an Indonesian beach to a design that harks back to the days of explorers and spice traders, although she is much more comfortable than the ships they sailed. The word “phinisi” is thought to come from “pinnace.” The word is French, and in the 17th century, pinnaces were small warships with two or three masts and a flat stern. The Tambora is one of the very few liveaboards that plies these seas and even she is only there for a few weeks a year. There are no land-based dive centres running dive trips to the area at the time of writing.

Soma Village

Our first dive of the trip was a muck dive-cum-checkout dive at Soma Village on the western side of Makian, another volcano in the chain that stretches down from Ternate and Tidore along Halmahera’s western coast.

The wall to the north of the village has some beautiful topography, a gorgeous colourful reef top, especially in the morning sun, plenty of fish and some wonders for sharp-eyed spotters to find. The jetty in front of the village is a great spot for night diving and makes a good day dive too. This is a critter dive. Start on the sand slope below the jetty and make your way up slowly looking for octopus, scorpionfish, pipefish, razorfish, flying gurnards, cockatoo waspfish, nudibranchs, various shrimps and crabs. Watch out for big, black, spiny urchins under the jetty itself and spend some time scouring the halimeda (green macroalgae) between the jetty and the shore for more critters. You will only be in about 2m of water here.

The Goraici Archipelago

We spent the next four days in the Goraici archipelago, diving first off the cape of Siko Island, then around a very distinctive double rock formation offshore, where we found an especially fabulous site that the Tambora calls Yellow Wall. This is best dived when the sun is high in the sky and when there is sufficient current running to open up all the coral polyps, bathing the wall in a sea of gold, like an underwater rapeseed field.

We also explored a number of seamounts elsewhere in the Goraici Islands. The diving was lovely everywhere: colourful soft corals plastered every rock larger than a pebble and each dive seemed fishier than the previous one. We saw multiple reef sharks at every site we dived, not a given these days anywhere in the Coral Triangle. In several places, tuna, wahoo and schools of surgeons, snapper and fusiliers buzzed us as we floated at the end of our reef hooks, watching the show.

We hardly saw any evidence of coral damage from dynamite fishing; the two patches we did come across were in the shallows. The rest of the seascape was untouched and several huge coral bommies looked extremely old. It was great to see such healthy reefs.

Kajoa Island

Our next port of call was Kajoa Island, where the best diving was on the northern side. Like so many islands in northeastern Indonesia, Kajoa is an exposed ancient reef, uplifted by tectonic activity.

Above water, among the twisted clefts and ridges, the rocks show the forms and fossils of ancient coral skeletons so clearly that you can identify which species they were. Below the surface, the same corals are alive and glowing in the sunlight. Pink soft corals hang over small caves, tall green tubastrea sprout from pinnacles and outcrops, and black coral bushes obscure small canyons in the reef. It really is a beautiful place, a paradise for wide-angle photographers.

The majority of the fish life can be found around the largest of the pinnacles, the top of which is at about 24m. Look here for schools of batfish, sweetlips, surgeons and black snappers, as well as blacktip reef sharks. In the shallows, there are some large caves in the rocks that snake enticingly as much as 50m into the island before the passage becomes too small and you have to turn around. Bring a flashlight.

Lata Lata Island

The next day, we were floating off Lata Lata Island, preparing to do a couple of dives on an undersea crater. It was 20 to 25m deep, with pillars in the centre, towering up almost to the surface, with steep walls around the edge. The pillars constitute a great dive on their own, but if you are up for a spot of hard finning, you can combine them with various sections of the outer wall. Follow the direction of the current or, if there is none running, just take your pick. Reef sharks are abundant all over the crater, as well as schools of fusiliers, snapper and sweetlips. There is lots of tiny stuff to be found among the coral growth on the pillars too: cowries, seahorses, pipefish and the like.

Penambuan, Bacan Island

For the first six days of our trip, the only people we saw were occasional passing fishermen in their outrigger canoes. We saw no divers or trawlers, and all the islands we had seen since Makian seemed completely uninhabited.

As we were far beyond the nearest phone masts, we were also out of reach of the world—Paradise. We realised our isolation was at an end when we saw phones appearing in the hands of the boat crew and spotted the village of Penambuan on the horizon. We were heading there not so much for a social media fix as to profit from some superb muck diving.

Penambuan is on the western side of the large island of Bacan, which is known for its semi-precious stones and is especially famous throughout Indonesia for having been the source of a particular stone presented to then US President Barack Obama, when he visited Indonesia.

There are critters aplenty among the sandy slopes all over Penambuan Bay, but the best site at the moment is the town jetty, where a rusted old freighter is tied up. The ship has made its last journey and now acts as a power station for this part of town.

After a couple of dives there, we debated whether the jetty was holding the freighter up or if the ship was holding the jetty up. As you cruise around the pillars of the jetty and gaze at all the marine life that assembles here, you see that some of the pillars have rusted away and now swing free in the gentle current, suspended a metre or so above the seabed.

On the hull of the ship, gorgeous, lush, soft corals obscure the metal completely and droop down into the water like a hanging garden of red, orange, pink, yellow, white and blue. Beneath this wondrous sight roam catfish, batfish and a couple of fat fish—large barracuda that evidently feed very well. Peeking out from beneath the junk on the seabed are an array of moray eels of different types. Besides the odd giant frogfish clinging to the sponge-encrusted pillars, there are stonefish, scorpionfish and crocodilefish galore, all happy to pose decorously and motionless for passing photographers.

The Batinti Straits

The final dives of this fantastic trip were in the Batinti Straits, between Bacan and the southern Halmahera mainland. The action centred around two islands, Proco and Nanas. Our first dive at Proco was relatively sheltered and very good for macro-photography, with a variety of pigmy seahorses to be found, as well as ribbon eels, jawfish, leaf scorpionfish and frogfish, but the second dive was much more dramatic in terms of both scenery and wildlife.

We had blacktip reef sharks accompanying us throughout most of the dive, the undercuts in the reef wall were full of lobsters and an enormous dome-shaped sand patch at around 27m was packed full of garden eels, as far as the eye could see. Farther along the wall, at a depth of around 18m, we found a small lava arch to swim through just at the point on the reef where the schools of fusiliers and surgeons were at their most substantial. Covered in soft corals, it made for an unforgettable image.

Tiny Nanas is home to a small group of fishermen who live in three stilt houses on the shore. The best site here begins in front of the houses and runs west along the reef to a sharp point. Features include a massive field of staghorn coral, big schools of fusiliers close to the point and lots of colourful soft corals.

Nanas is in the middle of the channel, so you can expect passing pelagics such as tuna and mobula rays, and we were lucky enough to see both! Blacktip reef sharks and great barracuda cruise the reef, and we had a school of batfish with us for part of the dive. On top of the reef, we found a patch of sand between outcrops where several jawfish had set up house and were all busy redecorating their terraces in some kind of jawfish “beautiful homes” competition.

Back to Spice Land

With the diving all done for this trip, we headed back to Ternate, with the Halmahera coastline to starboard and the string of volcanoes lined up with almost military precision to port. As the sun set over these iconic peaks, we thought about all the explorers, spice merchants, adventurers, soldiers and sailors, who in centuries past, had gazed in wonder at this very view from the decks of ships not so dissimilar from ours and marvelled, as we were doing now. For us, though, it would only take 24 hours to get home. Hundreds of years ago, it would have taken them months! ■