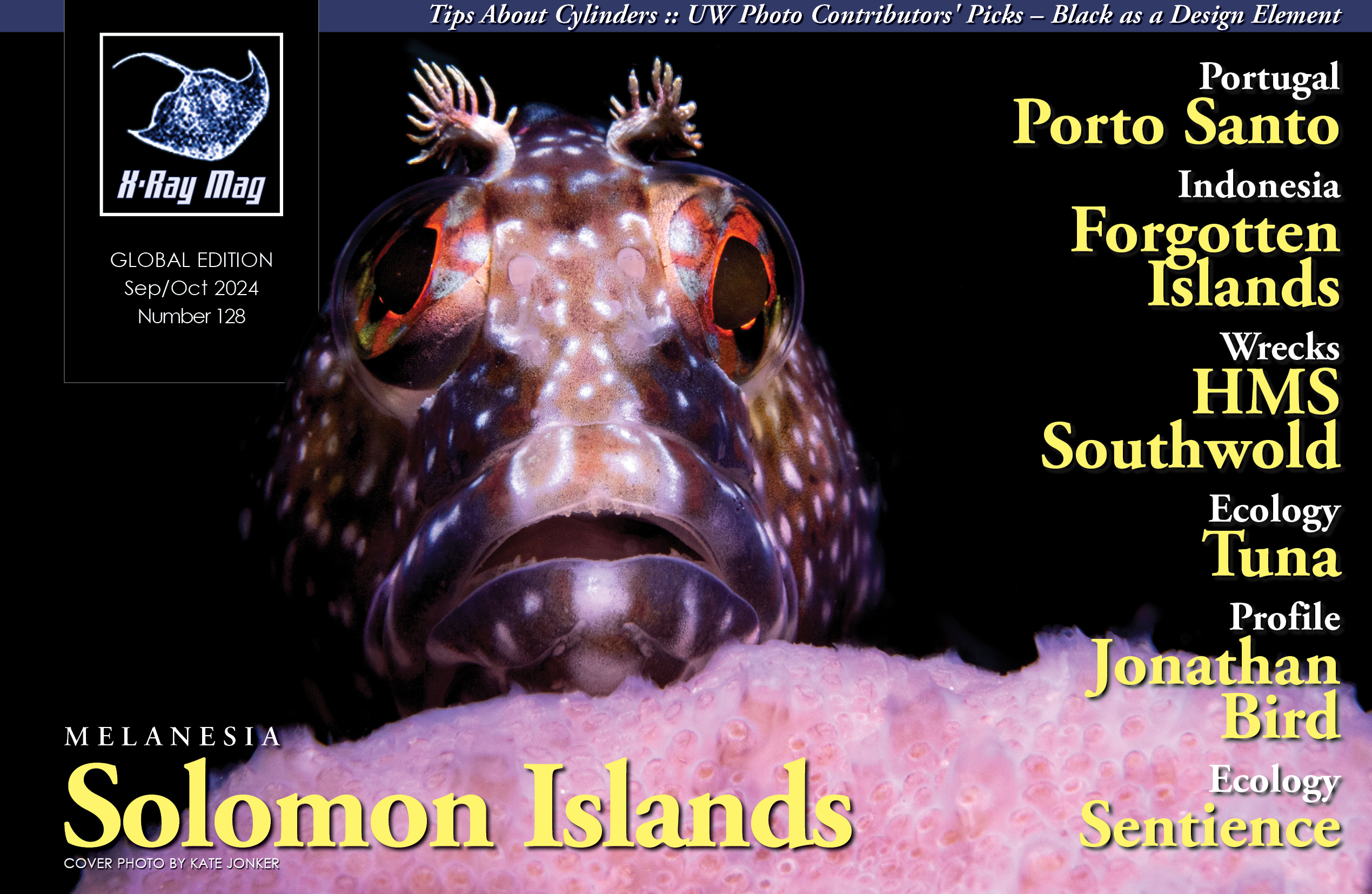

The Solomon Islands, located in the southwestern Pacific region of Melanesia, offer divers a plethora of underwater experiences, from pristine coral reefs to World War II wrecks. Matthew Meier tells of his return to this island oasis, where remnants of the islands’ military history can be viewed on land and under the sea.

Contributed by

I had the privilege of visiting the Solomon Islands in the summer of 2017, 75 years after Allied troops came ashore to launch the Battle of Guadalcanal on 7 August 1942. After nearly three weeks of amazing experiences, I reluctantly departed and vowed to return. In February 2024, I was finally able to do so, and this time, I was excited to introduce my wife to the remote beauty of the Solomons’ pristine coral reefs and the islands’ vast WWII history on display both above and below the water’s surface.

Returning to the Solomon Islands, I was curious to see what had changed, how the reefs had fared and what impact the COVID-19 pandemic might have had on the country. Like other Pacific island nations, the Solomons closed its borders to outside travel in early 2020 and was one of the last countries to reopen over 800 days later. Since then, the number of tourists has steadily increased, and for the first time ever, Guadalcanal even hosted the Pacific Games in the fall of 2023. The newly completed Honiara Sports City Complex was the venue for this athletic competition, which was a precursor to the 2024 Summer Olympics, featuring 24 teams from the region’s 22 countries and territories, plus a contingent of athletes from Australia and New Zealand.

Historical tours

Our adventure began with two days of land tours on Guadalcanal, visiting WWII museums, memorials and battlefields before boarding our liveaboard for ten days on the water. We had hoped to incorporate a couple of shore dives on local shipwrecks, but plans had to change when heavy rains created silty runoff from nearby rivers and creeks, drastically diminishing visibility.

Flights to Honiara via Fiji, the most direct route from the United States, currently land only three days per week, so divers will likely have a couple of days on the front and/or tail end of their dive trip to explore the area. I highly recommend scheduling flights to arrive early just in case there are any issues with delays or lost luggage.

Situated 15 miles (24.5km) west of the capital city of Honiara is the Vilu Military Museum. This jungle-esque, open-air facility is run by a local family who charges a nominal fee to walk among the numerous remnants collected after the war. The grounds are lined with Japanese anti-aircraft guns, cannons, machine guns, ammunition, the wreckage of several airplanes and multiple granite memorial monuments dedicated to the souls lost during the war. The experience is a fascinating glimpse into the island’s military history and well worth the bumpy, hour-long drive and the necessity for bug spray.

Near the museum is the final resting place of a WWII US B-17 (Flying Fortress) bomber, one of the wrecks we had hoped to dive. The wings, fuselage and cockpit remain nearly intact and lie just offshore in less than 60ft (18m) of water, where it came to rest after being damaged by Japanese fighters during a bombing raid on 24 September 1942. The tail section was removed and recovered in January 1944 by members of the 61st US Navy Seabees, and no human remains were discovered. Official records indicate that two of the eight crewmembers on board made it to shore after the crash, though neither survived long enough to tell their tale, and the fate of the six remaining crewmembers is unknown.

Wrecks and monuments

Continuing east, back toward Honiara, there are three shore-dive-accessible Japanese shipwrecks. They were all bombed by US aircraft on 15 October 1942. Closest to the B-17 is the Kyusyu Maru, a 466ft (142m) cargo vessel that ran aground after being bombarded. Initially, its bow stuck far out of the water, but over the years, it has succumbed to the depths, having withstood various salvage operations and possibly being the subject of target practice by US bombers after the war. The wreck is now completely submerged and lies at a 45-degree angle to the shore, from a depth of 10ft (3m) down to 148ft (45m). The Hirokawa Maru and Kinugawa Maru rest a short drive farther east, just offshore of Bonege Beach, with a small portion of the Kinugawa still protruding from the water.

On a hill west of Honiara and close to the current international airport (Henderson Field) is a monument to the Battle of Bloody Ridge, which took place 12-14 September 1942. Over the course of those two days, over 800 US Marines, under the command of Lt. Col. Merritt Edson, successfully repelled Japanese forces in a battle that was critical to maintaining control of two airfields, Henderson Field and Fighter One Airstrip, and with them the entire island of Guadalcanal. During the battle, the Marines suffered 57 casualties, and another 232 were wounded, while at least 1,214 Japanese soldiers perished. It is hard to put into words the somber feeling I had standing on that hill over 80 years later, with shallow foxholes still evident, trying to fathom what it must have been like to experience that kind of fear, devastation and loss of life.

The last site we were able to visit was the Japanese War Memorial, also known as the Solomon Peace Memorial Park. This simple yet elegant stone edifice and garden, located on a hill overlooking Honiara’s harbor, was dedicated in 1980 as a place of repose for all those who sacrificed their lives during WWII on Guadalcanal and throughout the Pacific Theater. If you know just where to look, it is possible to see the American War Memorial from the Japanese Memorial on a distant neighboring hilltop. We had hoped to tour the American Memorial the morning after our dive trip but had to postpone due to a torrential downpour.

Variable conditions

January and February are traditionally the rainy season in the Solomon Islands, and while climate change has made weather patterns less predictable around the globe, rain, wind and sea conditions forced altered plans several times during our trip—all part of the adventure and an important reminder to be flexible and curb expectations when traveling. Mother Nature is always going to win.

We boarded our floating home for the next ten days late in the afternoon on 30 January and proceeded with the usual introductions, paperwork, boat safety briefings and room assignments before reconvening for our first dinner together while still tied to the dock. The captain departed around 11 p.m. and attempted the open ocean crossing to the Russell Islands against a 9-13ft (3-4m) swell. For the next few hours, we drove west into the pounding waves before the decision was made to change course and head for the Nggela Islands, commonly known as the Florida Islands, in hopes of calmer seas. We were going to get a taste of WWII wrecks earlier than expected on this trip.

Florida Islands

H6K Mavis seaplanes. North and slightly east of Honiara, across the Iron Bottom Sound, are the Florida Islands. During the war, the Japanese had multiple strategic bases here, including one with over a dozen seaplanes, all of which were sunk as part of the secondary prong of the initial Allied invasion on 7 August 1942. Several of these H6K Mavis seaplanes have been discovered in subsequent years, and we had the opportunity to dive on wrecks numbered 5 and 6. Both planes rested in over 100ft (30m) of water and were amazingly well preserved after more than 80 years below the surface. I am happy to report that I did not see any major changes to either wreck since my last visit.

The huge wings of Mavis 6 were twisted on top of one another, tearing a hole in the fuselage behind the cockpit, allowing divers a peek inside at the intact gauges and the pilot’s yoke and seat. The float that once supported the right wing was now inverted and covered with soft corals, sponges and a huge school of glassfish. The nose cone of Mavis 5 was pushed upward, presumably from the impact with the sandy bottom, although the left wing was still attached with both engines in their mounts. The tail section had two impressive vertical stabilizers that were also intact; however, with the recent rains, our visibility did not allow us to see both at the same time.

Near the Mavis wrecks, we dived on the remains of a US PBY-5A Catalina seaplane that was sitting upright on the seafloor at 108ft (33m). Its wings were attached and resting on their floats, and the left engine had fallen off its mount and was propped up in the sand on two of its three propellers. Machine gun bullets were still visible along the rear fuselage, and the left wing was missing the same number of panels as it had seven years ago.

Garbage Patch. The Garbage Patch dive site in Tulagi Harbor was another captivating spot to see wreckage. Here, the bottom was littered with discarded tires, ammunition, scrap metal, oil barrels, anchors, entire ships and the bow of the USS Minneapolis, a WWII New Orleans-class cruiser. The port was used as a ship repair dock for many years, and what could not be salvaged was apparently just thrown into the water or intentionally sunk.

We made several reef dives to supplement the wreck diving around the Florida Islands, and I am pleased to report that the corals remain in excellent shape. The Solomons have some of the largest elephant ear sponges I have encountered, and they come in a brilliant purple color, as well as an orange and green variety. A number of them were easily over 10ft (3m) across, and we found a few that were inundated with a horde of white sea cucumbers. There were also large sea fans, huge domes of encrusting corals, a multitude of colorful soft corals and the always crowd-pleasing energetic baby sweetlips.

Russell Islands

After two days of diving, we made the overnight crossing to the Russell Islands through a series of scattered thunderstorms. Thankfully, the seas were a little calmer than on our first attempt, and the captain slowed our transit to allow for a slightly smoother crossing.

Located roughly 30 miles (48km) northwest of Guadalcanal, the Russell Islands consist of two small main islands surrounded by dozens of islets, all of which are volcanic. In 1943, as part of American military operations during WWII, the US Navy erected a large base in the Russells on the island of Mbanika and also established a supply base on the islet of Hai, code-named White Beach.

White Beach. One of three main supply depots used during WWII (Red, White and Blue), White Beach has become a dive site famous for the assorted equipment and floating piers that were dumped into the water at the war’s end. Here, divers will find trucks, jeeps, tractors, forklifts, bulldozers, ammunition and 80-year-old glass coke bottles, all encrusted with multicolored corals and sponges.

A few of the pier pilings were still intact, rising above the water’s surface, and the three submerged piers stretching out from the shoreline were clearly visible from the air. These unintentional artificial reefs appeared to be in similar condition after my seven-year absence, although a few had previously unseen colonies of green sea grapes growing across their structures.

Due to the sheltered nature of this site, we moored overnight and made a series of dives here over several days as the crew had to get creative with dive site selection due to weather restrictions. With repetitive dives, I was able to photograph a jeep resting upright at 120ft (36.5m), which we had not been able to locate on my first trip. Along the shoreline, archerfish could be found hunting among the mangrove roots, as well as a large school of diamondfish hovering in the shallow water column.

Another highlight for me was a night dive in search of flashlightfish. These deep-sea residents migrate to the shallows at night and are known to congregate inside one of the submerged piers. The dive produced at least four different species of crabs, numerous lionfish hunting among the rubble and a yet-to-be-identified octopus camouflaged against the substrate, but sadly, no flashlightfish.

Topography

Carved into the various islands and islets are an array of spectacular caves, caverns, inland ponds and cuts that have become some of the Solomons’ most iconic dive sites and are the result of the islands’ volcanic origins.

Leru Cut is perhaps the most well-known, consisting of a knife-edge gap in the rock of Leru Island, 10 to 15ft (3 to 5m) across, 30 to 40ft (9 to 12m) deep and extending 300 to 400ft (92 to 122m) into the island, with a canopy of trees overhead. The resulting thin vertical profile of blue water between black rock walls with a diver in silhouette is instantly recognizable. On a sunny day, there is a brief window of one to two hours when one can also see fabulous rays of light streaming down into the opening, although I have yet to witness that phenomenon in person.

Mirror Pond. Time of day is also key for light rays at Mirror Pond. This underwater cavern has a circular opening to the jungle overhead, which can produce fantastic images when conditions are optimal. It is a must-see during your visit. On my previous trip, our guide made a pre-dive check for “geckos” (aka saltwater crocodiles), which the current crew promised had not been seen of late.

Kastum Cave features a downward sloping underwater tunnel that opens into a 50 to 60ft (15 to 18m) high cavern with a small unobstructed view of the sky above, producing impressive floor-to-ceiling light rays when timing and Mother Nature cooperate.

Intervals and interactions

During surface intervals, life on the boat consisted of sharing dive stories and experiences with fellow passengers, rinsing gear, getting scuba tanks refilled, working on underwater cameras, occasional naps, reading books or playing card games, replenishing fluids and an abundance of good food. Most of the provisions were loaded on board before departing Honiara, but the chef was able to enhance the ship’s selection of fresh fruit, vegetables and fish by purchasing supplies from local villagers, who paddled out from shore in wooden dugout canoes in what is always a special encounter.

On one particular occasion, we had half a dozen canoes around the back of the boat, filled primarily with blond-haired children selling their wares. Solomon Islanders and other inhabitants of Oceania have a gene in their DNA that produces blond hair in roughly 5 to 10 percent of the population, similar to the percentage of blondes in the rest of the world; however, researchers have determined that the characteristic arose completely independently of European influences. It is a fascinating and beautiful trait.

Our original 10-day itinerary was to include a visit to Marovo Lagoon, which involved a lengthy overnight open-ocean transit to the west of the Russell Islands. The lagoon has fabulous coral gardens, including many species I had only encountered in this area, not to mention some of the largest sea fans I have ever seen. I had hoped to revisit a local village to spend time with and photograph the locals, learn more about their way of life and potentially augment my collection of ocean-themed wood carvings, as Marovo Lagoon has some of the best wood carvers in the world. Sadly, the sea conditions did not allow us to make the crossing safely. So, we spent a few extra days sampling the remarkable diving in the Russells, and the crew was also able to coordinate a local village tour. We were treated to a performance of traditional song and dance, and one lucky guest had an adorable child follow along, holding hands with them for the entire visit.

Bonus diving

We investigated dive sites that we would not have had the chance to see on the normal route, finding stunning coral gardens teeming with reef fish, huge sea fans, numerous species of clown fish, including the endemic white bonnet anemonefish, a large congregation of spawning surgeonfish and even a pair of mating whitetip reef sharks thrashing around on the seafloor. The reefs were very healthy, with only minimal signs of brown algae growth in a few select spots, and while I was unable to make comparisons from my previous visit, I would say that they had fared quite well during our absence.

Wreck of Ann. I was also introduced to a new shipwreck called the Wreck of Ann. It was an old freighter deliberately sunk as an artificial reef, stretching stern to bow from 30ft (9m) down to 100ft (30m) in the sand. The vessel’s cargo hold was cavernous, and there were lots of little critters hiding among the colorful coral and sponge growth on the superstructure, making for a fun dive.

Back to the Florida Islands

In an effort to shorten our final crossing home to Honiara, and hoping to get ahead of the worsening sea conditions, we made an overnight crossing back to the Florida Islands for one last day of diving.

Baby Cakes. Our first site was at a pinnacle called Baby Cakes, which I had navigated in a strong current during a night dive seven years ago. As luck would have it, we were in for a similar experience, as the dive guides explained that we would need to use the mooring line to pull ourselves from top to bottom.

Once down, we swam toward the point, into the current, in search of schooling fish, but along the way, I found one of my favorite photo subjects and never ventured further. Below me, perfectly nestled in a bed of red algae, was a gorgeous dark green crocodilefish. These ambush predators are prevalent in the Solomon Islands, and I saw four on my previous trip, but apparently, this time, I had to wait until our last day to be rewarded with this beauty. The struggles of pushing a large dome port into the current melted away as the opportunity to photograph this fabulous scene made it all worthwhile.

On the way back

After our last dive, the captain needed to move the boat into Tulagi Harbor so we could tie up safely for the night. The shortest distance was to the west into unprotected waters, which was initially attempted but quickly proved to be too rough. Thus, the decision was made to circle around the northern and eastern sides of the island before cutting through a long channel not typically utilized by vessels of this size.

We sailed slowly down the narrow passage, past small, secluded villages and children waving from the shoreline as the sky lit up in pink and orange hues as part of a fabulous sunset. This once-in-a-lifetime opportunity was so rare that the entire crew assembled on the decks to soak in the experience. It was an evening that none of us will soon forget.

Lasting impressions

The following morning, we were back in Honiara, saying our goodbyes to guests and crew before heading to our hotel for one last night before our flight home. As always, the trip was over far too soon, and despite the challenges, we thoroughly enjoyed our time in the Solomon Islands. I was glad to see that the reefs were still incredibly healthy, vibrant and isolated enough to keep them from being over-loved. Plus, I was relieved to know that the Solomon Islanders were able to endure the pandemic and were making a strong recovery. My wife and I look forward to a return visit and highly recommend that you explore the Solomons’ fascinating culture, rich WWII history and underwater wonders for yourself. ■

Thanks go to Master Liveaboards (masterliveaboards.com) for hosting this adventure, Tourism Solomons (visitsolomons.com.sb) for their help on the ground, arranging land tours and shore diving, and Scubapro (scubapro.com) for their assistance with underwater dive gear.