Sniffing out a deadly meal of microplastics

Seabirds use their sense of smell to seek out their next meal. However, in these times where microplastics are rampant in the oceans, sniffing out a meal may not be the best hunting strategy for seabirds.

This is because the harmful microplastics emit a chemical that is irresistible to seabirds as it’s the same as a compound that signals to them that prey is nearby. Seabirds in the order Procellariiformes—like albatross and petrels—seem to be particularly affected. They are almost six times more likely to consume plastics than other seabirds.

A research team led by Matthew Savoca from the University of California, Davis in the US made this discovery, which was published in the Science Advances journal.

These birds fly vast distances above the oceans, looking for signs of a chemical called dimethyl sulfide, which is produced by marine algae – especially when it is being nibbled on by little organisms such as krill. The presence of the chemical tells the birds that food (ala krill) is nearby.

Birds that use dimethyl sulfide for finding food are almost six times more likely to consume plastics than other seabirds.

Savoca and his colleagues believe that plastic debris provides a handy growing platform for the algae that produce the compound. After a while, the plastic may take on the chemical profile, attracting the seabirds.

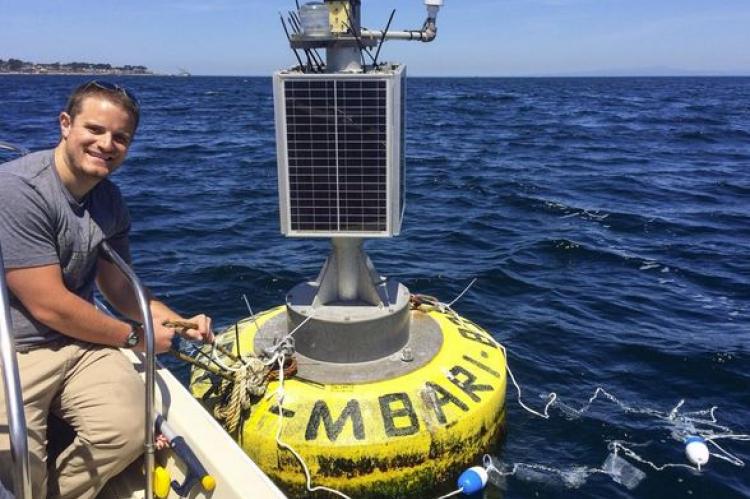

To test their theory, the researchers tied mesh bags of plastic beads made from three common plastics to a buoy. After three weeks, dimethyl sulfide was found on every piece of plastic and at levels that were easily detectable by seabirds.

While the seabirds eat plastic because it looks like food, chemical cues also appear to play a big part.

The research suggests other animals that share similar diets, particularly those that eat crustaceans like krill, might be attracted to the chemical signature that plastic debris takes on as well. Sea turtles, penguins, fish and even mammals have all been shown to use this chemical for feeding in some way.

Not only are these animals in danger of eating plastic, they are tricked into foraging in areas that don’t actually have many nutrients and thus miss out on real food.

The researchers hope that the discovery of how plastic debris operates within marine food webs can help us understand why many marine animals are affected and how to mitigate the plastic problem—starting with creating plastics that cannot accumulate dimethyl sulfide.