An article recently published by the BBC discusses the latest scientific findings on consciousness in animals. It states that not only do the “higher” animals, such as birds and mammals, appear to experience consciousness, but likely all vertebrates do. The cephalopod molluscs, including octopuses, insects and at least some crustaceans, are also mentioned as having shown evidence of consciousness. Ila France Porcher takes a closer look and provides insights into the cognitive lives of marine life.

Contributed by

But this is hardly new news. The evidence of intelligent awareness in animals has been steadily accumulating for decades. In particular, it was Donald Griffin’s work in the 1980s, followed by his book Animal Minds in 1992, that finally broke through the bias of mainstream science with the declaration that some actions performed by animals cannot be done without thinking (called cognition in animals). His book provides a fascinating array of examples of cognitive behaviour from species across the animal kingdom. He and his colleagues considered that cognition must require an overseer who is doing the thinking. Therefore, already at that time, some degree of conscious awareness was felt to be a necessary part of the mental life of animals using cognition.

Griffin’s work was met with virulent opposition from traditional scientists, for behaviourism dominated the field then. But I was greatly relieved to find my own observations backed up by his views. Watching from the sidelines, I had been appalled that scientists denied consciousness to animals while at the same time conjecturing that their computers would soon be conscious. Indeed, Daniel Dennett pronounced his thermostat to be conscious (in an intentional state) in 1978! His ideas were taken seriously by leading advocates of artificial intelligence (AI), including John McCarthy, who echoed his ideas in later writings.

However, their hopeful idea that complexity automatically produces consciousness, as in the human brain and complex computers, has been debunked for various reasons. For one thing, it forecasted that consciousness should spring up in places where most people would not expect it, such as in your CDs. Further, it excludes all other living things, as if complexity is more important than life. The quality of life, which is not yet understood, should not be so easily dismissed.

Reading down the page, the BBC article gives some interesting examples of intelligent animal behaviour, but then the word “consciousness” is suddenly dubbed a weasel word and replaced with the word “sentience”.

That struck a discord with me, for sentience and consciousness are two different things. The sentience of an animal (the capability to feel and to suffer) should undoubtedly be acknowledged and taken into account in establishing guidelines for animal welfare laws governing, for example, fishing, agribusiness and laboratory experiments. But “sentience” is not interchangeable with “consciousness”.

Many of the points made in the article come from the position of behaviourism, which has dominated thinking about animal mental states since 1924 when John B. Watson introduced methodological behaviourism, a technique that sought to understand behaviour by measuring observable actions. Behaviourists consider that no one can know what mental states animals might have, so each is considered a “black box”. But this human-centred position fails to consider the way all life evolved together on this unusual planet.

Behaviourism

In ignoring evolution, it smacks of Creationism. Indeed, behaviourism grew out of mechanical philosophy, which appeared in the 1600s and included the Christian belief that the human is divine and that God put the rest of nature here for us to use. Animals were classified as being mechanical in nature. This opened the door to vivisection, and within a short time William Harvey had discovered the circulation of the blood by cutting up animals alive. The trend continued.

The mechanical philosophy’s view of nature as being mechanical, and thus reducible to its parts, laid the groundwork for behaviourism’s reduction of psychological phenomena to observable actions while avoiding introspection or subjective analysis. Behaviourism therefore focused on behaviour that could be easily measured in laboratory experiments. An animal’s behaviour was reduced to simple stimulus-response associations termed “conditioning”.

What this all boils down to is that if a creature lacks a human brain, then whatever it might think or feel is irrelevant. This is the argument used to claim that fish cannot feel pain despite the vast wealth of evidence that they do. It is also used by various industries to perpetuate their control over the use of animals for profit.

Animals’ true nature

One gets a very different idea about animal behaviour by observing wildlife in their natural habitats. Watching from a distance, ethologists see what wild animals are actually doing and how they respond in different situations. Thus, they witness their true nature in action. Ethology also emphasises the role of evolution, environment and innate behaviours, or instincts. It acknowledges that each individual is different.

As a wildlife artist, I have observed a wide range of species in nature—reef sharks most extensively. All the wild animals I have known have shown evidence of being able to reason and hold an idea in mind while working towards a planned outcome. Such goal-oriented behaviour—assuming a future in the making and demonstrating learning from the past—suggests the presence of an overseeing, self-serving awareness doing the thinking. That is, there is a “self” or “I” that is considering what is happening, making moment-to-moment decisions and keeping his or her purposes in mind as (s)he pursues his or her life.

Though individual variations among animals are ignored in lab experiments, the essence of the evolutionary process is the natural behaviour of individuals. A community of a given species adapts to changes in its environment through the ingenuity and resilience of each member. For it is each one’s efforts and choices that drive evolution, as each succeeds or fails to reproduce and pass on its unique set of genes to its descendants.

It is self-evident that for an animal to survive, it must be able to understand reality accurately enough to respond to it appropriately, or it will go straight into evolution’s garbage can. And no brain is simple, as anyone who has observed the actions of a spider will appreciate.

Are they conscious? Has anyone ever produced any remotely convincing evidence that an animal can win the evolutionary fight without being conscious? No.

Consciousness

Consciousness, far from being a weasel word, is currently being studied by scientists from diverse fields. Though neglected for many decades while behaviourism dominated psychology, since 1994, interest in this “last frontier of science” has exploded. The science of consciousness emphasises broad and rigorous approaches to all aspects of the study and understanding of conscious awareness.

Sir Roger Penrose, a professor of mathematics at the University of Oxford, is one of the pioneers in consciousness science. In his first book on the subject, The Emperor’s New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds and The Laws of Physics (1989), he presented a beautifully crafted argument that computers would never be conscious because consciousness is not computable. He pointed out that many other things in nature are not computable either, including simple and evident things. For example, the sun and moon are visible to any creature on this planet—they appear circle-shaped. The ratio of the circumference of a circle to its diameter is pi, a number that a computer cannot represent.

Penrose theorised that consciousness is fundamentally a quantum-mechanical phenomenon. This came at a time when AI advocates were at the height of their hype about their soon-to-be-conscious machines, so he attracted a lot of attention. But so far, he seems to be right. By the early 1990s, most of the large AI labs had shut down because vast efforts to program the basic cognitive tasks by the most brilliant people on the planet had failed. No one could figure out how to present information to a machine and have it understood. Advances since then have been based on increased speed and complexity rather than new algorithms permitting machines to perform cognition.

Penrose’s approach to consciousness echoes that of the Athenian philosopher Plato, who first described a world we can access only through our consciousness. Only through reflection can we understand reality. Ideas unfold when we reflect upon them, and mathematical ideas have been found to underlie the actions of the physical universe. For example, anyone can reflect upon a circle, measure the circumference and diameter and try to figure out the number pi. More mysteriously, the universal constants, which include the speed of light, Planck’s constant and the speed of expansion of the universe (plus only a few others), are each extremely precise. These remarkable numbers underlie the reality that we know. And through reflection, many different scientists figured them out.

Three worlds

Penrose describes three realms: consciousness, the physical universe and Plato’s world. He calls the relationships between them the three profound mysteries. In the physical world, consciousness appears, reflecting and finding Plato’s world, the truths of which lie behind the manifestation of the physical world (Penrose, R. 2007. The Road to Reality. Vintage).

Music also leads us into Plato’s world, and some birds sing using scales defined by our own musicians. When played at one-quarter speed, a hermit thrush’s song is like a human composition, with between 45 to 100 notes and 25 to 50 pitch changes. It approximates a pentatonic scale with all the harmonic intervals. Many other species, too, compose their own songs and perfect them single-mindedly, apparently trying to match some inner concept of the musically beautiful, which they perceive in their minds—in Plato’s world.

The creations of bower birds, which in every way resemble art, provide another example of the recognition of the beautiful by an animal.

The lionfish presents an extraordinary loveliness that is thought to have evolved under the influence of its prey, crustaceans. What would that tell us about crustaceans?

Then there is the peacock. In its quest to become beautiful, it did not just grow a radiant plume to attract the gaze—it evolved a fabulous fan of intricately designed feathers, each detailed to the microscopic level, all fitting together to produce a breathtaking overall design.

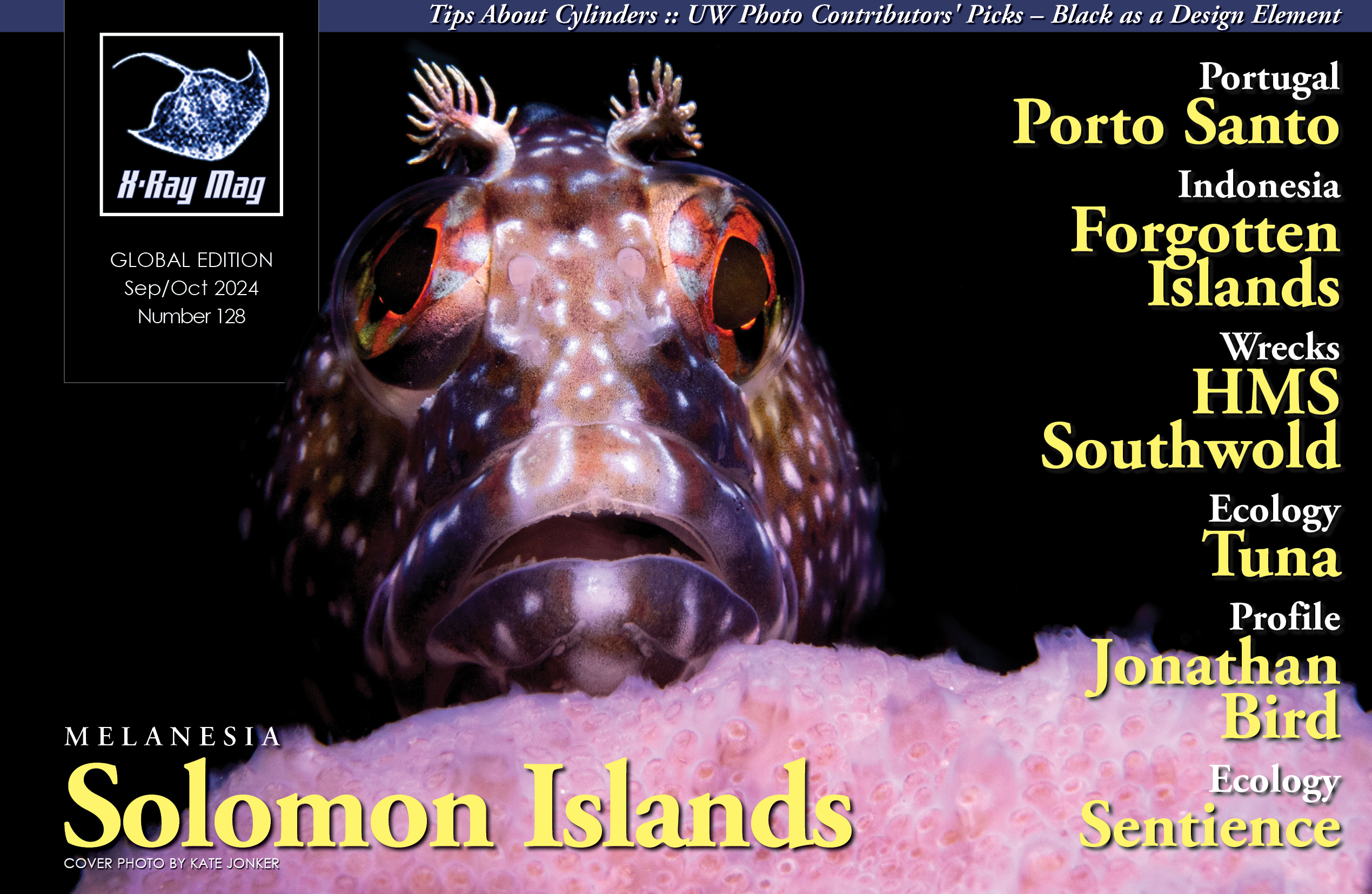

The intricate and precise colouration of many marine invertebrates is spectacular. Their flamboyant patterns tell us something about the minds of these ephemeral life forms who, through aeons of evolution, have chosen their dress.

The delicacy and beauty of the biosphere convey something of the underlying quality of the consciousness behind it. Indeed, the appreciation of beauty could be widespread in living things yet unperceived by us. So much of nature is beautiful that one could postulate that beauty was selected for. That is, animals chose beautiful mates, and therefore, the most beautiful individuals had the most offspring. The appreciation of beauty is an indicator of consciousness.

Awareness and thinking in animals and plants

Paramecia are one-celled animals, so they have neither brains nor nerves, yet they can learn, remember and make decisions based on whether they were in a place before and whether they had a good time when they were there. There is now evidence of rational behaviour in bacteria too.

The vast gulf that was thought to separate humans from animals does not exist.

The sensitivities of plants have also been well documented. Films of them in motion look uncannily animal-like when sped up. Researchers have found that plants show many of the same types of awareness and thinking found in animals. They are aware of their environments, including the location of other plants and, in the case of climbing vines, objects that they can use as they climb upwards. The Asian dancing plant will learn to dance to music if it is exposed to music repeatedly, and individuals improve with practice, suggesting learning and memory.

The modern view of plants is that they are a completely different form of life that evolved in another direction from the one taken by animals. Though plants lack organs, they send messages through their systems in the same way that nerves transmit information in animals. They are just as evolved as animals, and apparently, they are aware of reality in other ways.

Research into the inner workings of forest ecosystems has revealed that, far from standing alone, each tree networks with others through fungi, slime moulds and other species to share water and nutrients as needed. The slime mould (Physarum polycephalum) is neither plant, animal nor fungus but an amoeba and an underground inhabitant of temperate forests. Slime moulds connect with trees and distribute nutrients, showing that living things are not necessarily devoted exclusively to their own survival. The slime mould has cognitive abilities that have been assumed to depend on brain circuitry, and its intelligent behaviour is one of the unexplained mysteries of science. There are likely to be similar examples in the marine environment, so far unrevealed by science.

These findings suggest that intelligent awareness, or consciousness in some form, may be an intrinsic aspect of life—a comprehension of reality in which the creature, simple as it might be, understands its environment as it functions within it. This shared understanding becomes the ground for interaction among the vast and diverse network of living things that covers our planet from pole to pole.

Evolution

Reflection on life’s processes suggests other curious facts. While science holds that consciousness evolved from matter, religion holds that matter evolved from consciousness.

Let us consider how evolution works. The flight capabilities of birds have been documented through the fossil record to have evolved slowly as their ancestors tried to stay in the air for longer and longer spans of time. At first, just the ability to hop higher, with the forelimbs reaching up, must have begun the transition as the creature fled from increasingly nimble predators. Gradually, gliding developed, as only those who were able to leap the highest reproduced. At last, over aeons of strife by each individual trying to survive, wings evolved.

Thus, the behaviour came before the structure; birds have wings because they fly. Here, it is consciousness that gives rise to matter. Following this line of reasoning leads to a picture in which the species have created themselves, each being a manifestation of all the efforts of all its forebearers down through the abyss of time since life appeared. It was consciousness that created matter!

Thus, from many perspectives, there is evidence that we live on a planet full of conscious, thinking life forms.

However, so far, researchers have made very little progress in discovering what conscious awareness is. It has even been suggested that, from our limited perspectives, we are simply unable to understand it, just as fish cannot do mathematics. And consciousness is not the only enigma that remains. Life itself and how it appeared here on Earth is another deep mystery.

Therefore, with the source and nature of consciousness so elusive to science, there is absolutely no scientific basis for denying it to any living thing. ■

Further reading:

Dennett D. 1978. Brainstorms: Philosophical Essays on Mind and Psychology. CAMBRIDGE: Bradford Books/MIT Press.

Ghosh P. 2024. Are animals conscious? How new research is changing minds. BBC.

Griffin DR. 2001. Animal Minds: Beyond Cognition to Consciousness. University of Chicago Press.

Penrose R. 1989. The Emperor’s New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds and The Laws of Physics. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Penrose R. 1995. Shadows of the Mind: A Search for the Missing Science of Consciousness. Oxford, England: Oxford University Press.

Porcher IF. 2017. The True Nature of Sharks. Independently published.