In the world of technical diving, a direct ascent to the surface is not an option if you run into a problem or emergency. For this reason, technical divers are required to carry back-up systems to resolve problems associated with equipment malfunction during a dive.

But what about the rest of us?

Fortunately, there are a lot of good lessons and readily applicable techniques to be learned from the world of technical diving, that can make diving much safer, without being a real bother or overshadowing the experience. Using a seat-belt when driving a car has become second nature, as is carrying a spare tyre in the trunk. We will probably never, or rarely, actually have need of them, but when needed we surely appreciate these simple measures.

But here the similarities between driving and diving stops. Running out of gas when driving a car is mostly just an embarrassment and inconvenience, but for a diver, it can obviously have dire consequences.

The meaning of redundancy In dive-speak, redundancy usually translates into having double tanks, double regulators, double this and double that. But what does redundancy really mean? The dictionary give us the following definition.

Redundancy, in general terms, refers to the quality or state of being redundant, that is: exceeding what is necessary or normal, containing an excess. This can have a negative connotation, superfluous, but also positive, serving as a duplicate for preventing the failure of an entire system.

The last sentence in the above definition is interesting because it raises a very important question, also in terms of diving: When is something superfluous, and when is it an important safety measure ‘preventing failure of an entire system’? Most of us will probably agree that using a heavy double tank rig for a shallow water dive is overkill, and we wouldn´t be bothered. But as we go gradually deeper and longer, we will also approach a point where a double rig becomes a very useful piece of equipment and a safety measure

So where is this point?

Turning once more towards the above definition, the entire system refers not just to the mechanical equipment but also to the diver, along with his or her training and ability to cope with critical situations. For this reason, when to use then becomes a somewhat subjective and individual question. It is not, however, just a matter of what the diver can safely handle but also a question of mental comfort during a dive.

Diving, we should not forget, is also about having a good time. Simply bringing the extra equipment - even on dives that do not venture into those depth zones where conventional wisdom would deem it absolutely necessary – means more than just additional safety. Just as importantly, the feeling of having that extra safety also translates directly into making the dives far more enjoyable. Because, while it doesn’t lower any alertness, it does remove the latent stress-loading of what if...?. And this is certainly worth taking into consideration.

Being more concrete

So, are there no absolute criteria as to when one should wear back-ups? Absolutely! For starters, with any kind of diving that carries a decompression obligation, and diving in an overhead environment obviously qualifies, as set forth by various training agencies. But before it comes to that, why not make it a policy always to have a sensible margin of safety, and always use redundant systems for any diving close to the NDL limits or beyond, say, 30 meters?

What is needed?

Regarding deeper dives or dives with long bottom times, redundancy means diving with twin tanks and two sets of regulators. These tanks may either be independent or, which is more common, connected by a manifold. In either case, if there is a regulator malfunction on the bottom, there is a back-up system which can be switched to.

Size matters

The tanks should also be big enough, not only to carry enough gas to complete the planned dive, but also to give an ample reserve supply to handle any unexpected problems. How big this gas supply should be depends not only on the depth and the length of the bottom time, but also on the diver and a previously determined breathing rate. The gas used at the deepest parts of the dive may be either air, Nitrox (aka EANx, Enriched Air Nitrox), Heliox, or Trimix. For shorter or shallower deco dives, divers might opt for a single tank, with a redundant valve (Y or H valve), allowing the diver to use two regulators on a single tank.

If there is a problem at the bottom, the dive would be cut short, and the diver would make a controlled ascent, complete his decompression obligation, and finish the dive safely.

Buoyancy:

For divers using wet suits, a redundant wing system should be used as the buoyancy device. This means two independent bladders, usually in one outer shell, and with independent inflators. In the event of a buoyancy problem, i.e. the regulator supplying gas to the primary bladder, malfunction, or a problem with the bladder itself, or ruptured inflator hose, etc, the diver would switch to his back-up bladder, make a safe ascent, complete the decompression obligation, and finish the dive.

Divers using dry suits might consider their drysuit a form of back-up buoyancy. In this case, divers should consider the weight of the diving system (rig), compared to the comfortable lift capacity of the drysuit. Swimming up to assist the ascent could be considered appropriate in this type of emergency, but if the diver is too negatively buoyant, and have to fin too hard or for too long, it could lead to excessive CO2 loading. As the breathing rate goes up, any narcosis would intensify, plus an increased risk of CNS O2 toxicity.

When relying on a drysuit as a back-up buoyancy device, one should take the worst-case scenario into consideration. For example, a split bladder where all the gas is abruptly lost from the wing. Would the dry suit support the diver sufficiently to make a safe and controlled ascent from depth, through a series of decompression stops, accurately and without overexertion? If not, the diver should consider using a redundant wing system.

Another important question is, whether a well worn dry suit with weak seals will be able to retain a sufficient volume of gas for a safe controlled ascent. If the drysuit has sufficient lift, then having a redundant wing system seems pointless.

Try to avoid carrying equipment, which would not be used.

If necessary, simulate the problem in shallow water with nearly full tanks. Dump wing gas, and see if you can establish neutral buoyancy using the drysuit alone

Depth and time monitors (Depth-timers):

In this day and age of multi-gas Air/Nitrox and mixed gas computers, divers have the luxury of having a continuously re-adjusted schedule with them on the dive, based on exactly what they are breathing,. When using Depth-timers, or computers in gauge mode, divers should carry back-up tables to have a schedule outside the primary plan, in order to handle any emergency causing a digression from the primary plan. Even those divers who use multi-gas computers might opt for the additional security of back up tables and plans.

The downside of multi-gas computers is, they may encourage technical divers to rely on the ability to make new plans on the fly (during the dive), instead of making a structured depth and time plan before the dive. In spite of the risk of being considered old fashioned, I think it is safer to make a structured plan and do the required calculations using an appropriate decompression software before the dive and consider the deco schedule, as generated by the multi-gas computer, as a bail-out option. Whichever system you chose, multi-gas computer, Depth-timer or computer in gauge mode, you need at least two to accurately finish the dive in the event one malfunctions.

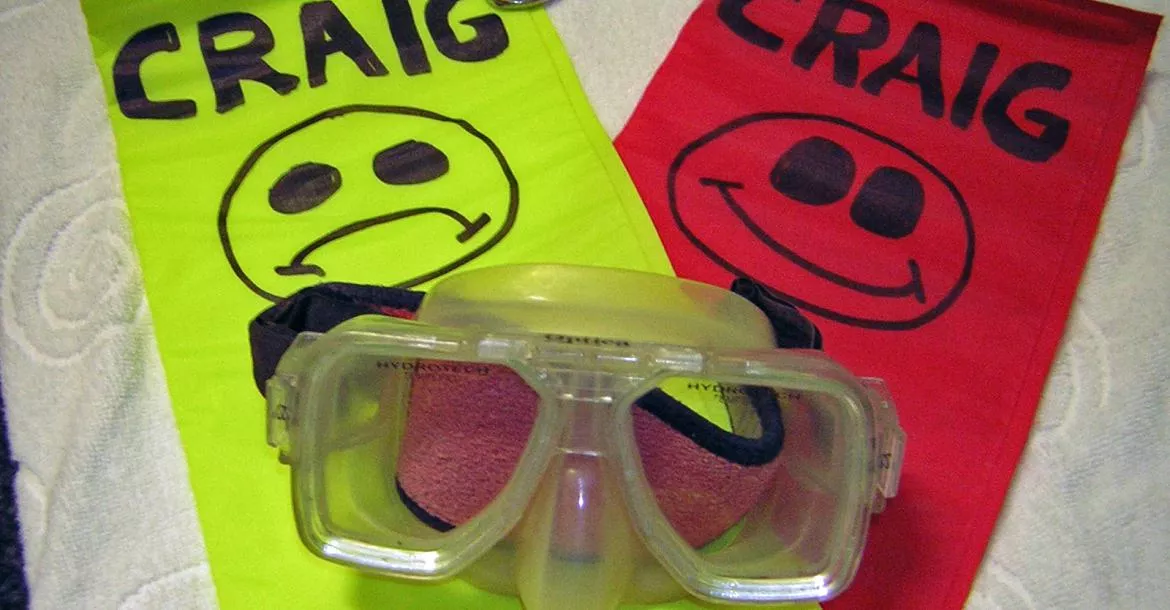

Mask

This is probably the most unlikely item of equipment you will have a problem with. But for any kind of dive that takes you into deep waters or a decompression schedule, you should certainly bring two. I can talk from my own experience, as I once lost a lens during a dive. This was due to a hairline crack in the frame of the mask, which went unnoticed at the surface before the dive. The backup mask came in most useful, enabling me to read gauges, whereby I could ascend at the correct rate, perform accurate stops and finish the dive safely.

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #4

- Read more about X-Ray Mag #4

- Log in to post comments