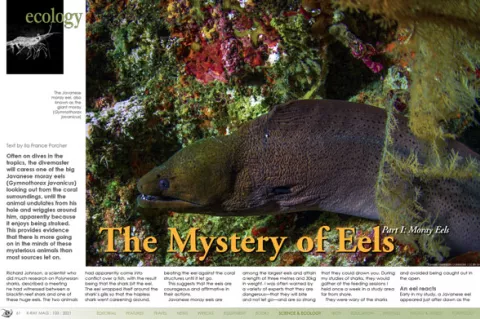

Often on dives in the tropics, the divemaster will caress one of the big Javanese moray eels (Gymnothorax javanicus) looking out from the coral surroundings, until the animal undulates from his hole and wriggles around him, apparently because it enjoys being stroked. This provides evidence that there is more going on in the minds of these mysterious animals than most sources let on.

Contributed by

Richard Johnson, a scientist who did much research on Polynesian sharks, described a meeting he had witnessed between a blackfin reef shark and one of these huge eels. The two animals had apparently come into conflict over a fish, with the result being that the shark bit the eel. The eel wrapped itself around the shark’s gills so that the hapless shark went careening around, beating the eel against the coral structures until it let go.

This suggests that the eels are courageous and affirmative in their actions.

Javanese moray eels are among the largest eels and attain a length of three metres and 30kg in weight. I was often warned by a variety of experts that they are dangerous—that they will bite and not let go—and are so strong that they could drown you. During my studies of sharks, they would gather at the feeding sessions I held once a week in a study area far from shore.

They were wary of the sharks and avoided being caught out in the open.

An eel reacts

Early in my study, a Javanese eel appeared just after dawn as the sharks were picking through their scraps. He took one of the pieces of food and put it in a grotto in the coral. Then he glided in his serpentine fashion back out into the open to take one of the biggest and best pieces of meat. These I had been lucky to get. Shark food was hard to find, but on this rare occasion, the fish shop owner had given me a few chunks of bonito meat that had become too old to sell.

I wondered if the sharks would do anything to protect their food. One of the juvenile males zoomed up to the eel in an intimidating gesture, but the other sharks ignored him. He was bigger than most of them. He retreated with his prize under the coral formation next to mine.

When the sharks circled away, the eel slid again from his hole, and targeted another choice morsel. So, outraged by his wanton thievery of the food I had gone to such trouble to procure, I swam over and waved my camera at him, indicating that he was to back off.

The eel undulated forward, gazing up at me gesticulating at him on the surface, and lifted his front half towards me. He opened his mouth with a venomous look one normally sees only in nightmares, and thrust his gaping jaws repeatedly in my direction, while waving slowly back and forth in the turquoise waters. I glared at him and he at me as sharks shot around us. When I returned to my perch, the huge eel glided into my coral formation and repeatedly thrust his head out at me. I had to retreat to another dead coral structure.

I continued to take notes and draw, but the lighting was not right for photographs from the only other formation available to hold on to. So, when a female shark who rarely visited approached, I returned to my original one, and waited, camera poised, for her to come close. But I had underestimated the emotional state of the eel, who now appeared under my nose, energetically trying to push himself through a hole just a bit too small to permit him to reach my face. I had to change locations again.

For the rest of the session, whenever I looked at the eel, he menacingly thrust his head towards me. It was daunting to see his emotional reaction and for how long he held his grudge! There was no doubt that he had understood my gesture when I had advanced and waved my camera at him. Though I had not actually attacked or chased him, he had fully understood anyway!

A cooperative eel

At the evening feeding sessions, the big eels were common visitors. Their heads waved from their retreats around the clearing in the coral, and they flowed like anti-gravity snakes from one formation to another as they manoeuvred to get a scrap. As the session passed, they accumulated around me and slowly moved closer. During the height of the warm season, there would be four or five spaced around me, equidistant from one another.

One began to linger in the labyrinths of the formation I habitually used as a perch and he would reach up from a deep grotto on my left as I fed the fish. Sessions passed, and he persistently lurked there, surprising me at unwelcome moments. Once I found him curved up under the overhang, his menacing smile opening and closing centimetres from my elbow, yet out of my view unless I leant over and looked there.

He was clearly aware of eyegaze. I had been putting my hand there repeatedly to drift scraps of fish meat to the fish, yet he had never bitten me. When I became aware of him, I began floating larger pieces to him, hoping to convince him of my benevolence. But I avoided letting my hand get near him again.

One night, as it grew dark, he began looking at me expectantly from the grotto. I was using the rectangular frame of a saumon des dieux or opah (Lampris guttatus) to feed the fish, and its flesh was tough, and difficult to scrape off for distribution to the hundreds of characters impatiently waiting. Slowly I worked, scattering the handfuls, and wafting pieces to the moray eel. From time to time, I was interrupted by the sharks and then resumed feeding the fish. Once in a while, the eel retreated, and the space filled with groupers and squirrelfish, all waiting for crumbs to come their way.

It was nearly dark when the eel reappeared and extended enough of his length from the grotto so that our eyes were on the same level. From there, he looked at me alertly and I looked back, wondering what was in his mind. Our faces were close together and there was palpable eye contact. Very slowly, he moved forward, his eyes fixed on mine, and gently took his side of the frame of the opah I was still holding. He began to pull it, with the slightest pressure, without breaking eye contact. It was as if he was asking if he could have it—the whole thing—and waiting to see my response. The heavy piece was about 35cm square. I let go, and he carried it gracefully into the grotto.

His behaviour was very different from that described by the experts. He seemed to understand my actions of providing a snack for those gathered, and his behaviour in the situation was reasonable and intelligent.

Cooperative hunting

Redouan Bshary’s review of fish cognition (2002) describes how these huge eels engage in cooperative hunting, which involves cognition and was considered unique to humans before it was seen in chimpanzees and dolphins.

At Ras Mohammed National Park in Egypt, Javanese moray eels were solicited by Red Sea coral groupers (Plectropomus pessuliferus marisrubri), and lunartail groupers (Variola louti). These large fish would come up to within a metre of where the eel was resting in its grotto and shake their bodies in an exaggerated gesture. Often, the eel would emerge and swim next to the fish, sometimes so close that they touched. Then, while the eel roamed through the tunnels in the coral formations, the grouper would wait for the escaping fish.

A tiny eel

Sometimes, a tiny eel would appear nearby during the fish feedings. One began looking out of a hole in the coral near my right hand, at times, and became increasingly confident there. I handed him bits of food in turn, while scattering crumbs for the fish. When they became excited, he would slip a long length of his body out and oscillate wildly back and forth like an insane snake, trying to bite them.

He was present at my right hand no matter which dead coral structure I was using, so he was there intentionally. Then, when I began feeding the fish, he would emerge from his tiny hole, grab some meat in the fish head I held, and yank with all his might. I would waft a piece his way, which he would snatch, then he would search around my hands for more. Occasionally, he would get himself entwined in my fingers. Nothing I had ever felt could compare with his softness. After a while, he began touching my fingers while I watched the sharks, but never when I was looking at him.

He too was aware of eye gaze.

The mysterious community

As night fell, the blackfin sharks would disperse into the coral surroundings until only the nurse sharks remained, languidly writhing around the open region in the coral amid the flitting fish. There were enough of them to carpet the site—two of over three metres in length, and about five that were not much smaller than that, plus a few juveniles. They would scrape and suck out the contents of the fish heads, wriggling all over as they did so, in clouds of sand, wrasses and yellow perch.

One night, one of them was lying under a coral formation, close beside an enormous Javanese moray eel. The two of them were touching all along their sides, the nurse shark eating, the eel looking calmly out at me. For two species renowned for their aggression and even for being dangerous, the sight was unexpected. It enhanced the feeling of being in a community in which a certain camaraderie existed, which was far from the blood-and-teeth, dog-eat-dog way that nature is usually presented.

All of those animals gathered in peace for each session, and there never was any aggression or fighting.

Occasionally, a much larger Pacific lemon shark swept in. Startled by the arrival of such a huge and unexpected guest, all of the fish, eels and sharks present shot directly away from him, so that his entry was highlighted by thousands of shining streaks radiating away from the place he had entered. (This flight of fish away from the centre, when startled by a predator, is called a flash expansion.) However, the lemon shark would just take a fish head and depart, whereon the peaceful gathering immediately reformed.

Though both sharks and eels have shown that they will respond with their version of anger to aggressive affronts, they also showed continuously, week after week, year after year, that they were reasonable and essentially peaceful.

Indeed, no human mind can conceive their true qualities. They are clearly more complex and noble than we have assumed and show every sign of being sentient. ■

Ethologist Ila France Porcher, author of The Shark Sessions and The True Nature of Sharks, conducted a seven-year study of a four-species reef shark community in Tahiti and has studied sharks in Florida with shark-encounter pioneer Jim Abernethy. Her observations, which are the first of their kind, have yielded valuable details about sharks’ reproductive cycles, social biology, population structure, daily behaviour patterns, roaming tendencies and cognitive abilities. Please visit: ilafranceporcher.wixsite.com/author.

Special thanks to Rico Besserdich (maviphoto.com) and Andy Murch (bigfishexpeditions.com).

REFERENCES:

Bshary R, Wickler W, and Fricke H. (2002). Fish cognition: A primate’s eye view. Anim Cogn 5:1-13

Johnson, Richard H. (1976). The Sharks of Polynesia. Les Editions Du Pacifique.