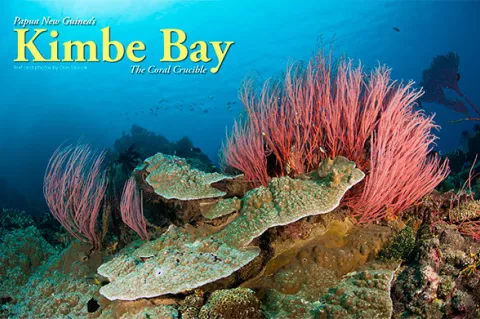

There is a line of thought in the scientific community that this is where it all began and the first corals originated… a large sheltered bay, roughly one third along the north coast of the island now called New Britain. The bay is called Kimbe and the country is Papua New Guinea—the wild and exciting nation crafted together in colonial times from the eastern half of the huge island of New Guinea and a string of other islands stretching out in to the Bismarck and Solomon Seas.

There can be no doubt regarding the profound fecundity of Kimbe Bay because the numbers, as they say, cannot lie and surveys by some of the best known names in marine biology, such as Professor Charles Veron and Dr Jerry Allen, and respected organizations like The Nature Conservancy, have helped to establish a bewildering array of statistics for the area.

Depending on which survey results are used, Kimbe Bay is host to around 860 species of reef fish, 400 species of coral and at least 10 species of whales and dolphins. To put that in a global perspective—in an area roughly the same size as California, Papua New Guinea is home to almost five percent of the world’s marine biodiversity. Just under half of that fish fauna, and virtually all of the coral species can be found in Kimbe Bay, which means that the bay can be considered as a kind of fully stocked marine biological storehouse.

Location, location, location

New Britain is part of the Bismarck Archipelago, which forms the southern ridge of the so-called Ring of Fire—the volatile and unpredictable, horseshoe shaped, seismic strip of oceanic trenches and volcanic arcs that wreak periodic havoc and destruction around the Pacific Ocean basin.

The islands of the archipelago were formed some eight to ten million years ago as a result of what geologists refer rather mildly to as volcanic uplift. The flight from Port Moresby into Hoskins Airport on the southern edge of Kimbe Bay will put the whole uplift concept into a slightly more dramatic perspective.

As you cross the narrow Vitiaz Strait from the main island of New Guinea, you will catch your first glimpse of New Britain, and you will see the western tip of a narrow crescent-shaped island roughly 500km long, by about 30km wide at its narrowest point and 150km at its widest.

Running along the spine of the island are huge mountain ranges, created by those volcanic uplifts, which are so high they effectively isolate the north coast from the south and create their own weather patterns, so that while the north coast follows the normal monsoonal seasons the south is completely opposite.

The mountains also create a partial rain shadow over the north, making the south coast the second wettest place on earth, with annual rainfalls of between six and eight meters.

The approach into Hoskins Airport takes you over the Willaumez Peninsular, the western boundary of Kimbe Bay, and provides a spectacular introduction to the other visually defining feature of this part of New Britain—volcanoes.

On the tip of the peninsular are two large freshwater lakes occupying the huge caldera left by the massive eruption of the Dakataua volcano some 1,150 years ago and then dotted along the long and narrow isthmus are three smaller volcanoes.

The final approach into Hoskins is overshadowed by the large Mount Pago volcano, and its two smaller siblings, whose periodic rumblings provide very poignant reminders of the powerful seismic phenomena far underground that created those volcanic uplifts.

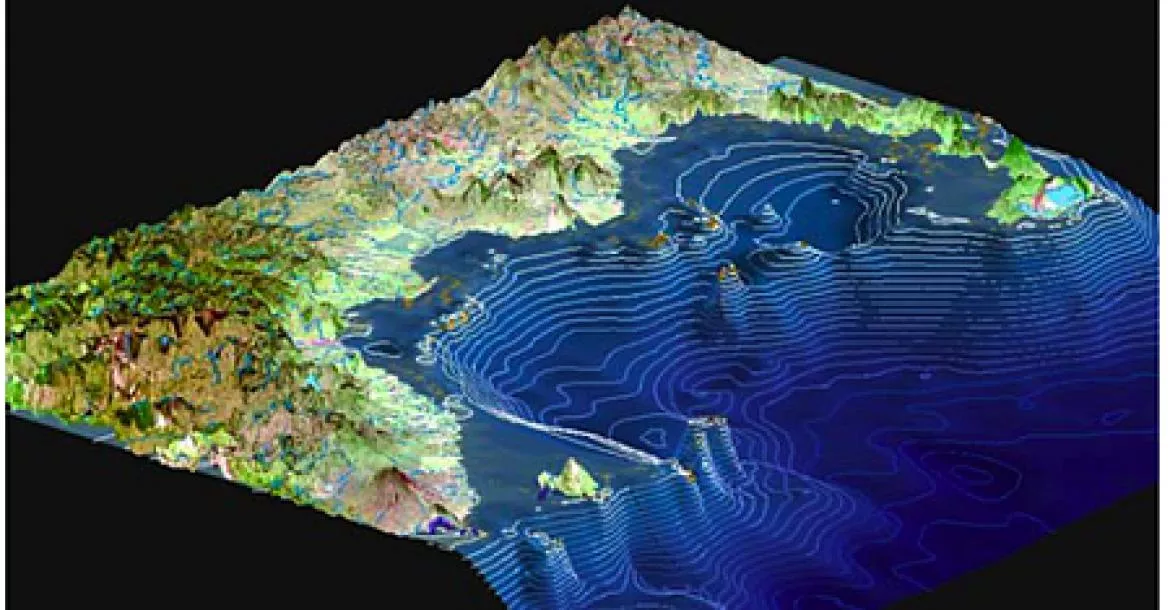

Beneath Kimbe Bay

Bounded by the long Willaumez Peninsular to the west and Cape Tokoro, some 140km to the east, Kimbe Bay is sheltered from the worst of New Britain’s weather. Along the coastal area of the bay, a 200m shelf runs parallel to the shore for about 5km before dropping down to around 500m and up to 1,000m in the eastern part. On the northern outskirts of the bay as it approached the Bismarck Sea, the seafloor drops off rapidly to in excess of 2,000m.

Across this deep seascape are dramatic seamounts and coral pinnacles that rise up towards the surface and provide isolated ecosystems for the marine creatures of the bay.

The seamounts in particular act as beacons to the bay’s diverse and prolific pelagics and marine mammals—with 12 species of mammals identified to date, including sperm whales, orcas, spinner dolphins and dugong.

The deep waters and generally benign conditions function as a kind of marine nursery and are fundamental to the incredible biodiversity of Kimbe Bay, but the other significant element are the nutrient-rich currents of the Bismarck Sea that provide the nutrients to sustain the bay’s residents and visitors.

To the south of New Britain are the 4,000m deep-water basins of the Solomon Sea which the Southern Equatorial Current crosses as it makes it way towards the Bismarck Archipelago. As this powerful current approaches the south coast of New Britain, it creates upwellings that suck up the nitrogen and phosphorous laden detritus of the sea from the deep basins.

Those nutrients are carried north through the Vitiaz Strait in the west, and the St Georges Channel (between New Britain and New Ireland) in the east, in to the Bismarck Sea where they enter the predominantly anticlockwise circulation produced by the regional current flows.

As those currents flow along the north coast of New Britain and around the top of the long and narrow Willaumez Peninsula, eddies are produced in the western part of Kimbe Bay that direct the nutrient rich flows into the bay and induce further upwellings from the deep water basins to the north.

In a nutshell, the incredible forces of nature have combined to produce an almost perfect natural environment to create and sustain the coral crucible and the creatures that cohabit with it.

Diving Kimbe Bay

Kimbe Bay is one of the global locations that most divers want in their logbooks. But it is a special kind of diving, as it’s not a shark-lover’s paradise or somewhere you go because manta rays or whale sharks aggregate at certain times of the year.

My personal definition would be “fish-bowl” diving, as it is like being immersed in a fully stocked aquarium, but with a considerable random factor of nature in that you never know what is going to come in from the blue—such as that day at Susan’s Reef, when I left three other divers on the deco line at the end of my safety stop and got back in the dive boat.

Vaguely wondering what was taking them so long, I am sure you can imagine my reaction when they eventually got in the boat some ten minutes later and very excitedly explained that a large sailfish had come in just after I left, and repeatedly checked them out before heading back out in to the blue again.

The random factor is particularly prevalent at the seamount dives such as Bradford Shoals, which is located on the very edge of the bay where the seafloor is some 1,500m below. Rising from that abyss to within 20m of the surface, its reef structure is mainly flat plates of hard corals, which are not particularly photogenic, however, amongst the plates are numerous colorful small reef fish—but very few divers go to Bradford Shoals to see reef fish, because it is what is above the reef that catches the eye.

Surrounded by deep blue water and quite distant from the nearest reef structure, Bradford acts as a magnet for big fish and pelagics. The sea is the sea and offers no guarantees, but on any given day you are almost certain to see large schools of barracuda, big-eye trevally, dog tooth tuna, unicorn fish and fusiliers. Add in to that mix the meandering but skittish white-tip reef sharks, the cruising gray reef sharks out in the current and the chance to see a great hammer head on an occasional foray up from the deep.

Then there is the visibility of often in excess of 40m, and you can probably understand how I came up with the name fish-bowl diving.

When to dive Kimbe Bay

Kimbe Bay is protected from extreme weather by its unique topography and access to the reef systems is available throughout the year. September through to the end of November sees calm seas and superb visibility in excess of 25m, but slightly colder water of 27°C, which usually more critters. December is changeable and hard to predict as the wet season approaches in January and goes through to March, bringing with it calm waters again and warmer waters around 29°C, but lower visibility around 15m. May through June is the doldrums with very flat seas, hardly any wind and clear skies. The water temperature goes up to around 31°C and visibility is in the range of 20m. July through August see the southeast trade winds start to blow at up to 20 knots, which means that the seas in Kimbe Bay can reach up to 1m and the water temperature starts to drop. Visibility is usually around 15m.

Preserving Kimbe Bay

When Max and Cecilie Benjamin arrived in New Britain in the late 1960s, they had only minimal interest in what was below the surface of Kimbe Bay, as they were agronomists whose principal focus was what came out of the ground, rather than the sea. Their assignment in Papua New Guinea was supposed to be a short-term one on their way to a new life in Canada, but all that changed when they bought the 800-acre Walindi palm oil plantation in 1969.

The intention was to modernize and improve the plantation’s operation, but by the early 1970s, they had started to scuba dive on the weekends and were literally the first people to discover the incredible biodiversity of Kimbe Bay. The rest is history, and in 1983, Max and Cecilie started Walindi Plantation Dive Resort, which has grown into a significant business complete with its own liveaboard dive boat capable of exploring the most remote locations of New Britain.

Walindi operates three day boats, each of which can accommodate six to eight divers and two to three dives per day, with two dives being the norm and the third available on request. Night dives are also available by arrangement. The dive boats leave about nine in the morning and return in the late afternoon with lunch being taken along and provided on one of the islands in Kimbe Bay.

The resort has 12 self-contained bungalows, each with its own bathroom and located just back from the beach under the shade of the many palm trees. There is a central area with a swimming pool and sun deck, dining room, lounge and bar area and the whole resort has a very pleasant laid back feel.

The Benjamins’ training as agronomists taught them to take a long-term and sustainable approach to their businesses, and by the early 1990s, they were seeing significant changes happening in the Kimbe Bay area, which if left unchecked could only degrade the pristine environment.

Up until the mid-1980s, the local population lived the same sustainable, subsistence lifestyle they had for centuries, with virtually no impact on the marine life of the Kimbe Bay. But by the end of the 80’s, it was becoming apparent that the development of the palm oil industry in New Britain was changing the traditional lifestyle in Kimbe Bay as economic migration into the area, along with high natural rates of population increase, had resulted in a steadily rising population density in the urbanized areas.

The increasing population placed far greater pressure on the local terrestrial and coastal ecosystems because of the rising demand for food, firewood and building materials plus a significant increase in pollution. Further compounding the situation, as new people and new ways flooded into the area, was the move away from traditional cultural practices, which had evolved over the centuries to support and enhance the sustainable subsistence lifestyle of Kimbe Bay.

In 1993, the Benjamins joined forces with the local government and The Nature Conservancy (TNC) to develop an overall long-term conservation strategy for Kimbe Bay, which would also support sensitive and sustainable tourism development in the area. TNC is a respected not-for-profit organization which came on board knowing that while Kimbe Bay faced environmental challenges going forward, it had largely escaped the ravages of cyanide and dynamite fishing associated with the live reef fish trade, which had wreaked so much damage to coral reefs across Southeast Asia.

The following year TNC, supported logistically by Walindi, conducted the first ever evaluation of the marine environment of Kimbe Bay to try and quantify its biodiversity. A Rapid Ecological Assessment (REA) was done with a specific focus on the coral reefs which, although considered to be little more than lifeless and indestructible rock formation by the native people of Kimbe Bay, play a very important role in local culture and mythology. The results of the REA were staggering as they revealed for the first time the magnitude of the bay’s marine diversity, with a total of 860 species of fish and 345 species of stony corals identified on the 78 sites visited.

To safeguard that incredible diversity would require an innovative and proactive approach, the key to which was education, for if the local people do not appreciate what is under the water in Kimbe Bay, how can they be expected to preserve it? A two-pronged strategy was developed consisting of the establishment of Mahonia Na Dari and Locally Managed Marine Areas (LMMA’s)

Mahonia Na Dari

—Reconnecting the Disconnect

Unusually for Papua New Guinea, the people of New Britain have a limited connection with the rich waters that surround the island—with few children learning to swim and many residents of inland villages never having even seen the ocean. Working together with TNC, and the EU’s Islands Region Environmental Program, Max and Cecilie Benjamin established Mahonia Na Dari (Guardians of the Sea in the local Bakovi language) in 1997 on land they owned next to the resort.

The goal of Mahonia is to develop and instill an awareness of Kimbe Bay’s unique environment so that its protection and conservation can become self-fulfilling, and it does this by educating the young people of the area through its Marine Environment Education Program (MEEP). The program takes students, many of whom have no experience whatsoever of the marine environment, out on the water where they can see things first-hand and better understand the need for the conservation and protection of Kimbe Bay.

MEEP has been very successful and has led to three student focused versions being developed: Baby MEEP for elementary schools, Junior MEEP for primary schools and Intensive MEEP for secondary schools, plus a Teachers MEEP to enable primary school teachers to conduct classes in their schools.

Since it was first established in 1997 it has been estimated that Mahonia Na Dari’s programs have benefited directly or indirectly in excess of 200,000 people have. As the old Chinese saying goes: “If you are planning for a year, plant rice; if you are planning for ten years, plant trees; if you are planning for 100 years, plant education.”

Locally Managed Marine Areas

Locally Managed Marine Areas (LMMA’s) are a well-established strategy throughout the Pacific Islands and are considered the best way to help local communities self-manage their marine resources in a sustainable manner and ensure a high degree of protection for the environment.However, in an area such as Kimbe Bay where the sea is considered an unlimited resource and reefs are thought of as lifeless rocks, LMMA’s in isolation would have little chance of success. The entire community has to embrace the concept for it to work and without the MEEP programs run by Mahonia this simply would not happen—hence the two-pronged approach.

Much has been learned since the first LMMA was established at Kilu next door to Walindi in 1998, and the village elders have proven to be a key ingredient to success as they usually understand intuitively the basic need for conservation and sustainability and will help to cascade the message down through the village ranks in the local dialect (Tok Ples).

A major obstacle to overcome as additional LMMA’s were established was the culturally intricate nature of the Kimbe Bay area, which has more than 100 socially diverse communities, with each one holding complex and often overlapping traditional rights to sea resources. So it was essential to establish clear boundaries for the LMMA’s and then quantify the initial situation through evaluations of coral growth, sea grass coverage and species count so that no-take zones to allow recovery on damaged reef areas and open areas where fishing is allowed can be established.

Another key component of the overall MEEP and LMMA programs was to halt and eventually eliminate the spread of poison rope fishing and prevent the encroachment of dynamite fishing. Poison rope fishing uses the Derriss Root, which grows naturally in Kimbe Bay, whereby the plant roots are smashed with a rock and then the fisherman swims down and sticks it in the corals. In the white pulp of the roots is the poison Rotenon, which kills small fish and coral polyps, but forces larger fish to the surface where they are easily caught.

Dynamite fishing is not the scourge of PNG it is in other Southeast Asian countries, but does occur in Kimbe Bay from time to time on an opportunistic basis using dynamite that has been “harvested” from WWII ammunition found in the rainforest and then shoved into SP beer bottles.

Funding for boats and engines by the provincial government enables the villagers to monitor their no-take and open area zones, and keep poachers at bay, while Mahonia provides periodic audits to keep the system honest and encourage sustainable fishing practices such as hand lines and spears. There are now a total of eight LMMA’s established in the Kimbe Bay area, with more planned going forward.

The Crucible

Papua New Guinea is very much a developing country but it is awash in minerals, amazingly diverse, physically stunning and surrounded by some of the richest waters anywhere in the world. It is also a difficult place to do business with a system of governance that leaves much to be desired. The perseverance of individuals like Max and Cecilie Benjamin to open up the wonders they find underwater in their backyard is admirable, but their sheer determination to protect and conserve it deserves a standing ovation. ■

Asia Correspondent Don Silcock is based in Bali and travels widely throughout Asia. His website has extensive information and image galleries on the diving in Papua New Guinea and other great dive locations across the Indo-Pacific region. Visit: www.indopacificimages.com