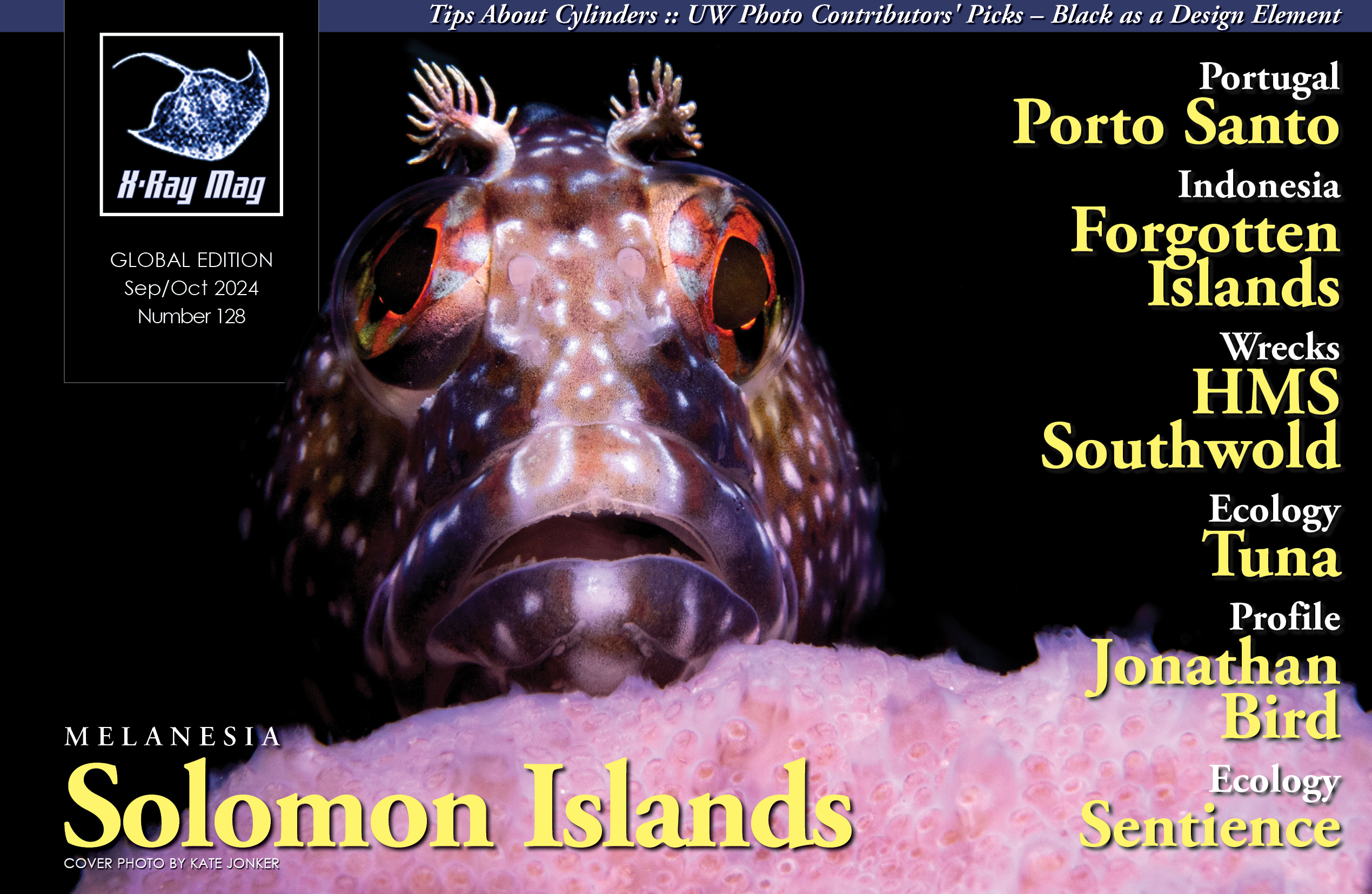

In the waters of Malta, an island nation in the Mediterranean Sea, there are several deep wrecks accessible to technical divers. One is the Second World War British destroyer HMS Southwold. Kurt Storms tells us about his dive on the wreck.

Contributed by

Malta, at last. This trip had been planned for some time, but due in part to a lack of time, it had never happened. When I was invited to represent Divesoft at Rebreather Forum 4 in Valetta, it was the perfect opportunity. Together with my dive buddy Willem (Wim) Verreycken, we set off for Malta to dive on some deeper wrecks, including the beautiful WWII wreck of the HMS Southwold.

The wreck

The wreck of the Southwold came to rest on the seabed in two sections. The bow section is the larger of the two. It is about 40m long and lies at a depth of almost 68m, entirely on its starboard side. The stern section is about 30m long and sits upright on the seabed at a depth of 74m. The stern is about 200m from the bow section, which means one has to do this wreck in two dives.

History

Commissioned on 20 December 1939, HMS Southwold was built by J. Samuel White and the Company of East Cowes as part of the British WWII emergency programme. Following the laying of the keel on 18 June 1940, the ship was completed on 9 October 1941 and launched on 25 May 1941.

HMS Southwold belonged to the Hunt class of destroyers. These destroyers were 86m long with a beam of 9.5m and had a net tonnage of 1,050 tonnes. Used as convoy escorts, they had a top speed of 25 knots. With a crew of 168, Southwold carried three 4-inch twin-barrel Mk XVI guns, one at the bow and two aft, as well as anti-aircraft guns and anti-submarine depth charges. On completion, the Southwold went to Scapa Flow for trials before joining the Mediterranean Fleet.

From 12 to 16 February 1942, the Southwold was part of an escort for the Malta Convoy MW9B, which never reached its destination. Of the three merchant ships, one was damaged and made it to Tobruk, but the other two sank. The Southwold and the other escorts returned to Alexandria, Egypt. On 20 March 1942, the Southwold left Alexandria to form part of the Malta relief convoy MW10 under the command of Admiral Sir Philip Vian. During the 820 nautical mile voyage to Malta, Southwold came under heavy attack from Italian warships and the Luftwaffe.

Once the enemy had located the Southwold, the Italian Navy was alerted and responded on 22 March 1942 by sending ten ships to the Gulf of Sirte (Sidra), 150 miles northwest of Benghazi, to wait for the convoy. When the Italian forces were sighted, Admiral Vian realised immediately that he was not only heavily outnumbered but also sorely outgunned. It was the Italian Admiral Angelo Iachino’s 15-inch guns on the battleship Littorio and the 8-inch guns on his cruisers against Admiral Vian’s 6-inch guns on the Alexandria and the 4-inch guns on his destroyers. So, to prevent the Italians from getting into range, the British decided to create a smoke screen. They then stormed in and out of the smoke screen, hitting their superior opponents with damaging salvos and dashing behind the smoke screen before the Italians could take range.

The fight was aborted that morning, but in the afternoon, the Italian squadron approached again. This time, Admiral Vian closed the range to below 10,000m, driving out of the smoke screen and managing to hit the Littorio with a salvo that set the battleship on fire. The Italians returned fire, hitting and severely damaging the British cruiser Cleopatra. The British destroyers, including the Southwold, quickly counter-attacked, emerging from the blanket of smoke and torpedoing the Littorio again, as well as the cruiser Giovanni delle Bande Nere, after which the Italians retreated.

History records this battle as the Second Battle of Sirte. Determined to prevent the convoy from reaching Malta, German aircraft took over the attacks. When the convoy was only 20 miles from Malta, the Germans sank the Clan Campbell. However, the convoy was now within range of fighter aircraft from Malta. Hurricanes and Spitfires flew out to protect the remainder of the ships.

On 23 March 1942, the merchant ship Breconshire in the convoy was hit by enemy fire and stopped a few miles off St Thomas Bay. The weather turned rough, and the Breconshire drifted helplessly towards the shore, but the crew managed to anchor the ship 1.5 miles off Zonqor Point.

The next morning, the Breconshire was found dragging its anchors on the sandy bottom, and the Southold was called in to tow it. While attempting to pass a line to the disabled ship, the Southwold struck a mine, which exploded near the engine room, killing an officer and four sailors.

All power and electricity had been cut, so the diesel generator was switched on. The engine room was flooded, but the water gushing into the gearing room was stopped by shoring up the bulkhead and plugging the leaks. The tug Ancienttowed the Southold, but the ship’s hull at the engine room split open on both sides up to the upper deck. The ship began to sink, listing to starboard as the injured were transferred to the destroyer Dulverton.

Rocked by the swell, it gradually sank further and further amidships. The crew then abandoned the ship as it sagged more deeply, eventually submerging and breaking in two.

Diving

For wreck diving, we would go by boat, employing the services of Jason Fenech of Dolphin Cruises Boat Delfino in Malta. His modernised Luzzu boat, Delfino, is a traditional Maltese vessel fully equipped for technical diving. Jason’s knowledge of the wrecks is extensive, and he has no difficulty in locating the deeper wrecks and, most importantly, where to drop the shot line in the right place at the right time.

We were well-assisted by deckhand Karsten, who stepped in as a support diver. This job was important. If anything went wrong during the dive, he could jump in the water with extra tanks.

Today, we would be diving the bow of the Southwold. Using my Divesoft Liberty SM CCR, I would be doing the dive with my regular dive buddy Wim.

On the captain’s signal, Wim and I jumped into the water, and we drifted through the current to the shot line. Once there, we signalled each other to start the descent. I went first, followed by Wim.

After three minutes of descending, we reached the wreck and immediately proceeded to the back of the broken-off section of the vessel. We had a look inside and did our rounds. As agreed before the dive, Wim set up some lights so that this part of the wreck was a bit backlit. Wow, what a tremendously beautiful wreck it was!

We found some empty shells from the gun a few metres away. This double gun immediately caught our eye. It stood out, still as proud as it ever was.

Our bottom time was not very long. We only had 35 minutes of bottom time before we had to start our ascent and complete our 90-minute mandatory deco stops.

But before we went back up via the shot line, I took a few more photos of the prow, which was nicely lit on its side. Satisfied with some great photos, we signalled to each other that it was now time to begin our ascent.

In order to fulfil our decompression obligations as well as possible, we used a deco station. The last diver up disconnected the deco station from the shot line so we could all do our deco stops together. This way, Jason only had to keep an eye on the two red buoys instead of several surface marker buoys in different places. Doing decompression at a deco station is also very relaxing for divers. The deco station gave us a reference point to keep track of our depth. It also had spare tanks attached to it in case we had a gas problem.

After completing the deco stops, we emerged satisfied, and Jason approached with the boat. Karsten lowered the lift so that we could get back onto the boat with all our bail-out tanks without any problems. Happy, like a couple of kids, we ticked this wreck off our to-do list. ■

Sources: calypsosac.org, heritagemalta.mt, wikipedia.org