Rare centuries-old wreck found on Sweden’s western coast

Last autumn, maritime archaeologist Staffan von Arbin and his team discovered a very old wreck outside Dyngö, just outside Fjällbacka in Bohuslän (Bohus County). It later turned out to be a real find, but in fact, they were looking for a different wreck.

Interview and text by Mimo Moqvist

Translation edited by G. Symes

“Yes, it is actually a slightly special story. We were really looking for a completely different wreck, from the 16th century. As early as 2005, I got in touch with a man whose father had found a wreck outside Dyngö when he was fishing for trout,” said von Arbin.

The father who found the wreck was no longer alive, but the son tipped off von Arbin about the find and told him that he had material that von Arbin and his team could see.

“His father had salvaged a large frame, which was lying under a tarp in the garden. We did a tree-ring dating of the wood, which indicated that it was from the early 16th century,” said von Arbin.

Finding the wreck

In the fall of 2021, von Arbin and his colleagues dived at Dyngö to try to find the wreck. By surveying the area with drones, they found a structure in the water that looked promising. They showed up at the scene and found a wreck.

“We understood quite quickly that it was not at all the ship we were looking for, but that it was at least as interesting as the 16th-century wreck—if not even more interesting,” said von Arbin.

Permit and carbon dating

Shipwrecks dating before 1850 are ancient remains and may not be moved without a permit, so von Arbin contacted the county’s administrative board to get permission to take samples for a preliminary age assessment—which they received. A carbon-14 dating indicated that the ship could be as old as the 12th or 13th century. The method gives a rough dating, so they applied for a new permit to do a more accurate tree-ring dating.

The sampling was done at the end of November and von Arbin got a little more data on the ship, as they got more samples. But they had to wait a few months before they got the carbon-dating results, which came in February this year. It turned out that the ship was built between 1233 and 1240, with wood from northwestern Germany.

“Tree-ring dating, or dendrochronology, is a very good method for finding out the age and origin of a ship. There exist reference chronologies to compare with, and in general, there are very good references for oak, and to some extent pine, which is very fortunate, as most old ships are built of just oak,” said von Arbin.

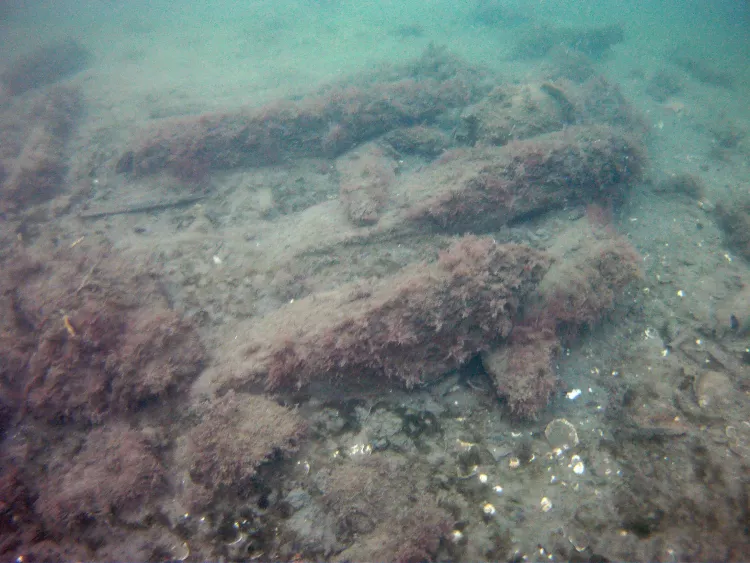

“The whole wreck is full of charred wood, so evidently, it had been subjected to a fierce fire. Maybe that is why it is there. Shipworm has been hard on the parts of the wreck that are exposed, but it is a lot more preserved in the bottom sediment. The wreck is about 10 by 5 metres, but originally, we estimate that the ship may have been about 20 metres long, which is a fairly large ship for that time.”

Further investigation

The hope is to eventually be able to make a larger investigation of the so-called Dyngökoggen (Dyngö Cog). But it requires a lot of planning, preparation and financing. It is not only personnel and equipment that is costly; during an excavation, the finds must not only be examined but also preserved. If it can be demonstrated that there is scientific value in an excavation, then there is financial support that can be applied for.

“It will be an archeological puzzle we put together, which gives us historical knowledge; we would, in part, get a better knowledge about the type of ship, which can help illuminate the development of the cog, because Dyngökoggen is one of the oldest found, and we might gain knowledge about why it is where it is,” said von Arbin. “Even if it has burned, we may be able to find out what was shipped, and based on that, we can deduce where it came from and where it was going.”

Von Arbin has been working in maritime archaeology for more than 20 years but has mainly worked with contract archaeology (or rescue archaeology), which means that he conducts research before, for example, new ports are built, dredged or something similar—just as an archaeological survey is done before any big construction on land.

“But right now, I am also working on a doctoral dissertation, on medieval shipping in Bohuslän. So, it suited me very well that I found this wreck right now,” said von Arbin.

Significant find

Dyngökoggen is one of his most significant finds.

“I have, of course, found a lot over the years, but never something this old,” said von Arbin. “We may not have realized at first that it was so old and that it was a cog, but we understood that it was actually a really old find. These are the moments you live for as an archaeologist—when you get an exciting result or make an exciting discovery. That is what drives one, and to be able to solve this puzzle that I talked about. Then, of course, it was extra fun because it fits so well with the dissertation—to find Bohuslän’s oldest wreck!”

The 16th-century ship they were actually looking for has not been found yet either.

“It would be fun to eventually find it too. But right now, the cog feels even more exciting to move forward with, of course,” said von Arbin.

Fact file

ABOUT COGS

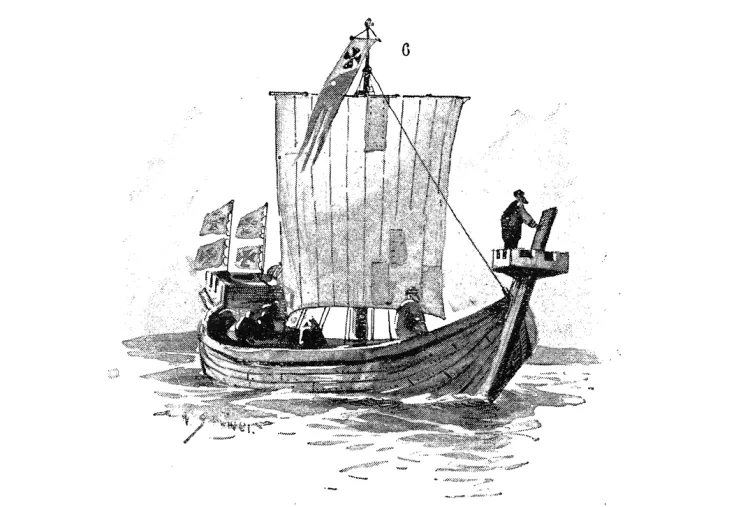

The cog was a type of ship that dominated shipping in Northern Europe during the period from 1150 to 1450. It was characterized by a box-shaped, flat-bottomed and load-bearing hull, upright bow and stern, carvel-built bottom and clinker-built sides, and a square mainsail on the centrally placed mast.

It is often associated with the northern German Hanseatic League’s trade successes during the Middle Ages. The type of ship is mentioned in written sources and is depicted on seals and paintings but is also known from about 30 wreck finds from all over Europe. The Dyngö Cog is one of the oldest cogs ever found and the seventh to be found in Swedish waters.