From the capital city of Copenhagen, across the Great Belt to Funen and the Little Belt to Jutland, travelling through the green fields of the Danish countryside, Scott Bennett describes his diving and dining adventure through Denmark, stopping along the way for a five-course meal at one of the 25 Micheline star restaurants found across the country.

Contributed by

Factfile

Drysuit Newbie: Taking the Cold-Water Plunge

I will be honest; when it comes to cold water, I am something of a wuss. With most my 900+ dives regulated to the tropics, cold water diving is a concept that usually fills me with trepidation. I have managed some dives in the Great Lakes in Canada as well as South Africa. On the cool side to be sure, I managed just fine with a 7mm wetsuit.

However, diving in Denmark often calls for a drysuit. With such experience nil (an unsuccessful attempt one January in Copenhagen, notwithstanding), this would prove to be something entirely different. However, new experiences are a good thing, and pre-conceived notions are not. Besides, I had the perfect dive buddy to help me along. It was time to take the plunge.

Donning in the field

Trying on gear in the store was one thing but getting ready on location was an entirely different animal. It was strange to consider I was wearing track pants and t-shirt that would not be getting wet inside the suit (in theory, anyways, but more on that later). After putting on the shell, Peter showed me how to apply baby powder over the rubber seals at the neck and wrists to make them easier to get into. Boots were attached to the suit in one piece, but the gloves were separate wet gloves.

Weight

My weight belt was in the form of a shoulder harness that effectively balanced the 30 pounds required. Factor in the 15-pound steel tank and it made for some serious heft. The 45 pounds of combined weight belt, plus one tank, ensured I did not move too quickly. My tank was attached to a BCD, but I would not be using the latter for buoyancy. I could not help but think that if I was wearing a 3mm wetsuit in the tropics, I would be already in the water photographing stuff.

Underwater, but dry inside

When one is not used to it, the feeling of being underwater, yet dry inside, was decidedly odd. Once in the water, overall flexibility was noticeably reduced compared to a wetsuit but not uncomfortably so. The biggest difference was the lack of a BCD. The inflator on the suit itself was easy enough, but the control valve just behind my left shoulder took some getting used to. Not particularly difficult, mind you—just different.

Bouyancy challenges

I found the hardest part was maintaining buoyancy with the control valve. Just turning one’s shoulder a certain way was enough to release air from the suit. That is, if you open it properly before going underwater. On a few occasions, I mistakenly had it closed instead of open. I had been warned that too much air in the suit can result in floating upwards feet-first. And yes, it happened. Several times.

Flooding the suit

In the end, everything that could go wrong, did. Flooding the suit due to an improperly closed zipper was probably the absolute low point for embarrassment, but I was assured that it happens to everyone. Another very minor flood occurred due to an improper seal on either a wrist or the neck.

In retrospect, these mishaps proved to be a good thing. These were all situations I needed to know how to deal with. Gearing up was cumbersome at first but got progressively easier. By the final dive, the stars aligned, and everything went perfectly. Goodbye trepidation, hello cold water. I’m hooked! ■

Gl. Ålbo

On the Jutland side, or the western coast, of the Little Belt, Gl. Ålbo Camping is equipped to cater for divers. Cabins with lockers for dive equipment, a diver-friendly jetty and a filling station has made Gl. Ålbo a popular resort—especially among divers from Germany, which is just a couple of hours’ drive away.

Luxury huts & fine dining nearby

Denmark currently does not host dive operations in which diving and accommodation is offered in one package, as is popular in many other countries, which may be the biggest obstacle holding back dive tourism in Denmark from becoming properly established. However, Gl. Ålbo is one exception, where everything is provided in just one spot in front of an excellent house reef and fine dining is not far away.

While not a five-star resort, Gl. Ålbo does have modern luxury huts (with up to six beds, loft, kitchenette, bathroom, heated floors and a deck) and an 8-bed/2-bath holiday cottage, which are comfortable and clean, with opportunities to mix with other divers. See: Gl-aalbo.dk

Drive to fine dining restaurants in nearby Bjert (11 minutes), Kolding (25 minutes) and Fredericia (45 minutes), including the Micheline-star New Nordic Cuisine restaurant Ti Trin Ned. See: titrinned.dk

Free Little Belt Guide

Did you know that Little Belt has one of the densest populations in the world of the smallest whale on earth—the porpoise? Learn more about Little Belt's nature, dive sites, beaches, tours, activities, food, restaurants, lodging, arts and attractions in the free 112-page e-book (in English/German/Danish) at: e-pages.dk/jfmadhoc/912/

“We’re going to Middelfart??” Now there was a name to draw out my inner 8-year-old. It's funny because it has “fart” in it! Chuckles over and composure regained, my interest was piqued. Having been sidelined earlier in the year due to an unexpected health issue, I was eager for a dive trip. When X-Ray Mag's editor-in-chief, Peter Symes, suggested his home turf of Denmark, I was a bit hesitant. As someone weaned on the tropics, the country does not exactly leap to mind as a dive destination. After all, isn’t diving all about coral reefs overflowing with colourful reef fish? What could possibly entice me to dive in water cold enough to transform my fingers into arthritic claws?

I had visited Copenhagen before, but had never been outside the city, let alone dive. Located 209km (130mi) west of Copenhagen in the central part of Denmark, Middelfart is situated at the western end of the island of Funen, just across the Lillebælt (Little Belt), the channel separating it from the peninsula of Jutland. With an area of 3,099.7 sq km, Funen (or “Fyn” as it is known in Denmark) is the country’s third-largest island.

Nothing to do with flatulence, the name “Middelfart” is derived from the Old Danish terms mæthal (middle) and far (way), referring to the Snævringen Strait, Little Belt’s narrowest section. It is also renowned as one of Denmark’s prime diving locations, attracting not only residents but visitors from neighbouring Germany and the Netherlands. I would soon discover it to be a very different kind of dive experience.

After a day to recover from jetlag, it was time to get ready. Peter managed to borrow a trailer to tow behind his car. Loading it with dive gear and luggage was a major undertaking. I had doubts as to whether the car could even pull it! Happily, the car managed, and we set out for the three-hour drive to Middelfart. Best of all: no worries about airport check-ins or excess baggage charges.

The journey

Getting there required a traverse of the Danish archipelago. Of the 443 islands, we had to cross two. Departing Copenhagen’s bustle, we soon entered the green of the Danish countryside. Dotted with numerous farms, it looked remarkably like rural Ontario, my home province in Canada.

We then passed over the Great Belt Bridge connecting the big islands of Zealand and Fyn, an engineering marvel that was the largest construction project in Danish history. Encompassing a road suspension bridge and a railway tunnel between Zealand and the small island Sprogø, located in the middle of the Great Belt, and a box girder bridge for both road and rail traffic from Sprogø to Fyn, the suspension bridge features the world’s third longest main span (1.6km or 1mi) and is the longest outside Asia. Prior to opening to road traffic in 1998, the only way across from Copenhagen was by ferry.

Diving 2000

Enroute to Middelfart, we stopped in the city of Odense to visit the dive center Diving 2000 where we picked up tanks and gear. Odense is famous as the birthplace of Hans Christian Anderson, and the city has many reminders of this distinction for the visitor. Despite spending most of his life in Copenhagen, both cities tussle over ownership of Denmark’s most famous literary son.

On hand to meet us at the dive center was owner Jan Laurenborg Olsen, who promptly fitted me with a shell and the latest Waterproof drysuit. Very snazzy indeed! We also picked up some tanks and added them to our already packed trailer. I was amazed the car could pull it all.

Lodging

After another hour, we finally arrived at Middelfart. Our home for the week was the Fænø-Sund Conference Center, a sprawling complex of identical yellow bungalows occupying a waterside location just outside of town. Our cottage was bright and spacious, with two bedrooms and bathroom, a living room, kitchen and outdoor patio—sort of like an Ikea cottage, with white walls and black furnishings. The spacious back courtyard was promptly occupied with our mountain of dive gear. Arriving on the cusp of the school holiday season, the resort was not yet full.

By the time everything was unpacked, it was getting past dinner time, so we headed into town to see what was open. Not a lot, as it turned out. Fortunately, Café Jazz, situated right on the waterfront was open, but we had to order fast. We all enjoyed a tasty smoked salmon salad as the sun set behind the Old Little Belt Bridge.

Culinary adventure

The next day began with a culinary adventure: lunch at a Michelin-star restaurant. Our reservation was for noon (the only available spot for days) and the drive just over an hour. Being a serious foodie, my anticipation was off the charts.

Set near Jutland’s west coast, the small village of Henne Kirkeby seemed an odd place for a Michelin-star restaurant. “What’s it doing way out here?” I asked Peter. “The chef is something of a rock star,” he replied with a grin.

Said star was Englishman Paul Cunningham, a man boasting some serious culinary credentials. As the former executive chef of the now closed Michelin-rated restaurant “The Paul” in Copenhagen’s Tivoli Gardens, he has cooked regularly for the Danish Royal family.

Pulling up stakes to head to Jutland, the master chef now fronts Henne Kirkeby Kro, a 300-year-old thatched heritage inn renowned as one of Denmark’s top dining venues. Serving up field-to-fork gourmet cuisine with vegetables from the restaurant garden, combined with artisanal local produce, the inn draws legions of loyal fans undeterred by the three-hour trip from Copenhagen.

Five-course affair

Behind the historic façade was an interior that was cool and contemporary, with crisp whites augmented with artistic flower arrangements and eclectic framed prints. Our waiter described the mélange of courses, with the menu reflecting what was in season.

We all opted for the set lunch of five courses with corresponding glasses of wine. Although trying to watch my diet, especially regarding fried food, I figured if I was going to throw caution to the wind, this would be the place!

First up was an appetizer of a beef tartare topped with a quail’s egg and tartlets (a favourite of the Danish royals) served alongside a salad topped with edible nasturtiums. A tomato salad featured five different types of tomato including, green, cherry and heirloom, all harvested from the restaurant garden. The freshness was superb.

Next up, cod braised in rich stock was seasoned to perfection, served alongside garden-fresh green peas and Danish new potatoes. Chef Cunningham’s fish and chips was a splendid take on the traditional British favourite. Flying gurnard coated with a feather-light batter paired with crisp chips further tantalized the taste buds. Dessert was a strawberry-rhubarb compote with mascarpone ice cream, a thoroughly decadent way to finish.

We were then treated by a visit with the man himself. Clad in striped apron and Danish slippers, Henne Kirkeby’s guru cut an imposing figure. Tall, bald and bearded, his smile reminded me of the infectious charm of comedian/actor Ricky Gervais, along with a very English sense of humour. “You’ve come a long way for fish and chips,” he quipped.

Garden tour

After a cappuccino and biscuits on the terrace, the chef led us out back for a tour of the gardens. No mere plot, the operation was extensive, complete with a small greenhouse. Ruby-red strawberries, tomatoes, gooseberries and edible flowers jostled for space alongside a multitude of herbs. It doesn’t get any fresher than that! Chef Cunningham’s passion for food has not gone unnoticed. Since our visit, the restaurant has added another Michelin star.

Beachside

Bellies full, a short drive brought us to Henne Strand, a holiday town right on the coast. Stretching to the horizon in both directions, the powdery-white beach was imposing and thronged with holidaymakers unfazed by the unseasonable coolness. No diving here, however, as the North Sea remains shallow for quite a way out.

Jelling

A drive across the Jutland countryside brought us to Jelling, a small village with some big history. A 10th century Viking settlement, Jelling was a royal monument during the reigns of King Gorm the Old and his son Harald Bluetooth. (Yes, just like the wireless tech, which was indeed named after him). In fact, the roots of the present Danish kingdom can be traced back to Gorm the Old in a continuous line.

Dating from the transitional period between Norse paganism and Christianity, the site featured two massive royal grave mounds and the Jelling Church, a 12th century structure in the traditional chalkstone style. The adjacent churchyard is home to the Jelling stones, carved runestones bearing Denmark’s best-known runic inscriptions. The older stone was erected by King Gorm in memory of his wife Thyra while the larger was raised by Harald Bluetooth in memory of his parents. Unfortunately, both are now encased in glass, courtesy of a drunken college student’s late-night graffiti binge.

A hike up to the summit of the larger mound provided superb view over the entire area. With the glorious late afternoon light, it was a perfect photographic end to the day. A nearby supermarket was open, and we stocked up on pickled herring, blue cheese, smoked salmon and salads for dinner back at the house. Not that we needed much after our sumptuous lunch.

White Nights

Being the time of “White Nights,” dinner was later than usual. As Denmark is positioned at a much higher latitude than Toronto, it did not get dark until well after 11:00 p.m. Even at midnight, a sliver of light illuminated the horizon. I suspected sleeping in would not be an issue.

Dawn came around 4:00 a.m., and outside my window, a cuckoo called, sounding like, well, a cuckoo clock. With car loaded and my trepidation mounting, we set out on the hour-long drive to Fyn’s southern coast.

Ærøsund wreck

Our destination was the M/F Ærøsund, Denmark’s last train ferry and newest wreck. Here we would hook up with fellow diver Lars, who was bringing a group down from Odense. Most of the journey was by expressway and the Saturday morning traffic was light. Arriving at the park, we passed holiday caravans parked on the grass, the weekend campers unfazed by the cool weather. The Odense group had already arrived, and Jan was giving a briefing. The moment of truth had arrived!

Located in the Ringsgård Basin near the village of Ballen, the Ærøsund was sunk in a controlled scuttling in October 2014. Beforehand, the vessel had been decontaminated and made safe for diving and marine life. By June 2015, a steady growth of vegetation started to appear, and within a few months, the wreck had become heavily overgrown. Today, the Ærøsund is one of Denmark’s most renowned artificial reefs. Positioned 550m from shore at a depth of 19m, the uppermost section (the funnel) is only 6m beneath the surface, making the wreck accessible for both freedivers and scuba divers.

With Peter’s patient assistance, I managed to gear up with minimal difficulty. The weather was 16°C and overcast, not particularly summer-like. On the other hand, the coolness was a blessing; we would not broil in our layers and black drysuits while waiting to dive. The extra 45 pounds of combined weight belt plus steel tank ensured I did not move too quickly.

The divers had brought along two zodiacs, which would take both groups to the ferry. Nevertheless, after double and triple checks, the moment of truth had arrived. Waddling to the jetty, I wondered how I was going to lower myself down to the zodiac. The answer was cautiously and slowly. Climbing down from the much higher jetty was a challenge, but I made it.

Getting there required took only five minutes. We were in the second smaller group and waited for others to go in first. A backwards roll and I was in. The water was not as cold as expected—a balmy 16°C. Not bad for such a northern latitude. Right away, I noticed the water to be less buoyant than the ocean. Technically part of the Baltic Sea, the water was more on the brackish side and less salty.

Diving the wreck

For the first dive, we concentrated on the main deck, so I could practice basic buoyancy skills. As it was my first time out, I opted to leave the camera behind. Due to recent rains, visibility was minimal, limited to only a few metres.

The vessel featured large openings for divers to swim through, with two yellow buoys anchored to iron chains to help divers locate them. The ballast remained in place, helping to stabilize the ship’s upward position on the sandy bottom. The wreck’s lowest portion was covered with mud and difficult to swim through without stirring up silt.

Finning around at a depth of five metres, marine growth was surprising, especially considering the wreck was just a few years old at the time we dived it. Clusters of yellow sponges were prevalent, adding a splash of colour. Some fish darted about, but moon jellyfish were especially numerous. Fortunately, they did not sting—a good thing, as a few brushed across my face. All in all, everything went rather well, and I looked forward to the next dive.

Unfortunately, it proved to be rather abbreviated. After my back-roll entry, I felt a surge of cold water rushing up my legs. Flood! As surface chop had intensified, getting back aboard the zodiac was a real struggle. Out of breath and feeling sheepish, I waited for the others to finish their dives. Peter soon resurfaced, and I explained what happened. “Don’t worry, it happens to us all once!” he responded cheerfully. “All part of the learning process.”

With diving finished for the day, we decided to take the scenic route back to do some photography. Pastoral vistas abounded; thatched roofs crowned traditional farmhouses, while orange poppies added vivid splashes to the surrounding fields. Fields of golden wheat rippled under a cobalt sky, the occasional tree interrupting the horizon. (Read more about diving the wreck in the following story on the sinking of Ærøsund).

Svendborg sojourn

Later in the afternoon, we stopped at Svendborg, a picturesque city nestled on Funen’s southern coast. Established in the 12th century, the city is the gateway to Funen’s southern archipelago. A shipbuilding hub for generations, the world’s largest container ship company, A.P. Møller-Mærsk, had its origins in the city. Today it is a major sailing centre, with more Danish boats registered than anywhere else outside of Copenhagen. Each summer, the country’s yachting elite inundate the cafe-dotted streets.

Thurø

First, we made a detour over to nearby island of Thurø. Around Denmark’s shallow bays, it is possible to find artefacts dating back to the Stone age and Peter wanted to show me such a location at Thurø Sund (Thurø Sound). The area was residential, with rambling old-style homes adorned with thatched roofs. Parking the car, we strolled down the lane towards the water, but it all appeared to be private land. A local homeowner asked what we were doing and then kindly invited us to walk through his property.

His home had been in the family for five generations, and they had been fisherman. One separate structure turned out to be the old smokehouse where fish were hung to dry. Although fishing had ceased years earlier, they now possessed some seriously expensive real estate! Although we did not find any arrowheads, the walk along the water was very picturesque. A dive-bombing seagull added some unexpected drama.

Thurø Sund is also unique biologically. Although meadows of carbon-storing seagrass are found in coastal areas worldwide, biologists have concluded those at Thurø Sund (sound) to be the most efficient found anywhere. This carbon-storing trait is garnering serious attention from scientists searching to reduce CO2 emissions into the atmosphere.

Downtown Svendborg

Back in the city, we had a wander around the downtown center’s pedestrian mall. Despite being Saturday, it was the pre-dinner lull, and the streets was largely deserted. Traditional architecture of wood and stucco flanked the cobbled streets while back courtyards revealed sequestered-away restaurants and shops. Some of the older buildings lacked right angles. Skewed and colourful, they proved especially photogenic.

DIY mentality

Arriving back at the resort, I faced something that was entirely new to me: We had to fill our own tanks. Although the resort did not have an actual dive shop, there were facilities onsite to fill the tanks. This trip was a true do-it-yourself endeavour and a rude awakening to those accustomed to extending a foot and having someone put a fin on it. (Like me!)

After a long day, we did not feel like cooking, so Peter’s trusty iPad located us some pizza takeaway. Babylon Pizza proved a real cross-cultural establishment: a pizza joint, with a Middle Eastern name, run by Tamils. The enormous meat-lover’s pizza was excellent! The next day was a literal washout, as it continuously poured with rain. It proved to be a good time to rest and do some photo editing.

Tides

With the Danish archipelago obstructing water passage from the Baltic to the Atlantic, channels between islands funnel tremendous amounts of water, and Little Belt was no exception. Currents at high tide can be especially fierce, surging up to three knots. Knowledge of incoming and outgoing tides is imperative, but a government website (https://ifm.fcoo.dk/select/index.html) produced by the Department of Defense’s Centre for Operative Oceanography (Huh?) came to the rescue. Peter bookmarked it on his iPad, so our dive sites could be chosen accordingly.

Fænø Sund

The next day we headed back to Fænø Sund, only a few minutes drive from our cottage. This time, we could park adjacent to the site, so getting gear to the water’s edge was far more expedient. Hovering around 19°C, temperatures were cool for June, but most comfortable when sitting in a drysuit during our surface intervals. Conditions were calmer too, so the dive would be a lot easier with a simple shore entry. I opted to go without the camera to concentrate on improving my drysuit skills.

Visibility was a bit murky on the surface but cleared as we went deeper. The sandy bottom was punctuated with weeds and more crabs than I have ever seen in one place. Along with a multitude of mussels, the sand was buzzing with tiny gobies. We even startled a small flounder, which promptly vanished in a flurry of sand.

Feeling confident, I took the camera for the second dive. Although less flexible than a wetsuit, the drysuit did not hinder my photography. The crabs were tolerant, so I could get close to shoot some portraits. One was eating a freshly caught shrimp, its headless body firmly clasped in one pincher. The gobies were more skittish, but I still got some images. Peter pointed out some anemones, which were the smallest I have ever seen. Like tiny red jewels, they were a stark contrast to the muted tones of the sand.

New Little Belt Bridge

Checking the tides for the next day, we decided on a site on the Jutland side, close to the New Little Belt Bridge. Conditions were perfect, with almost no current and a glassy surface. With gearing-up time quickening, I felt confident as I entered the water. However, the dive gods had other plans. My release valve was jammed, and I could not deflate the suit. Bobbing helplessly on the surface, I felt like the Michelin Man. So much for the dive…

A quick trip to Dive 2000 was required to remedy the problem, and Jan took care of it pronto. It turns out that late the next afternoon, he was taking a student out for an open water dive at Søbadet, a site near our resort. We agreed to meet up. It was a plan. Heading back, we decided on another dive at Fænø Sund as it was close to home. I especially enjoyed photographing the anemones along with some appealing white starfish tinted with hues of yellow and red. We later headed back to photograph the sunset. Crimson and orange tones set water and sky aglow, while in the opposite direction, a huge full moon ascended. The time? Eleven o’clock, and we still had not eaten dinner yet.

Søbadet

After a leisurely start the next morning, we headed to Søbadet (The Sea Bath), situated near the Old Little Belt Bridge. Renowned as one of the area’s premier dive sites, it is not only popular with Danish divers, but with visiting Dutch and Germans. We parked in front the old sea bath house, a distinctive yellow building about 30m from shore. Carrying all our gear to the water took some serious effort!

A small jetty made a great spot to gear up, with only a short swim to the deeper water. Søbadet is one of Denmark’s sole “multiple-level wall dive” sites, and just offshore, the dive area is indicated by large yellow buoys.

Large numbers of moon jellyfish pulsed off the jetty. As the tide slackened, many became stranded in the shallows to ultimately wash up on shore.

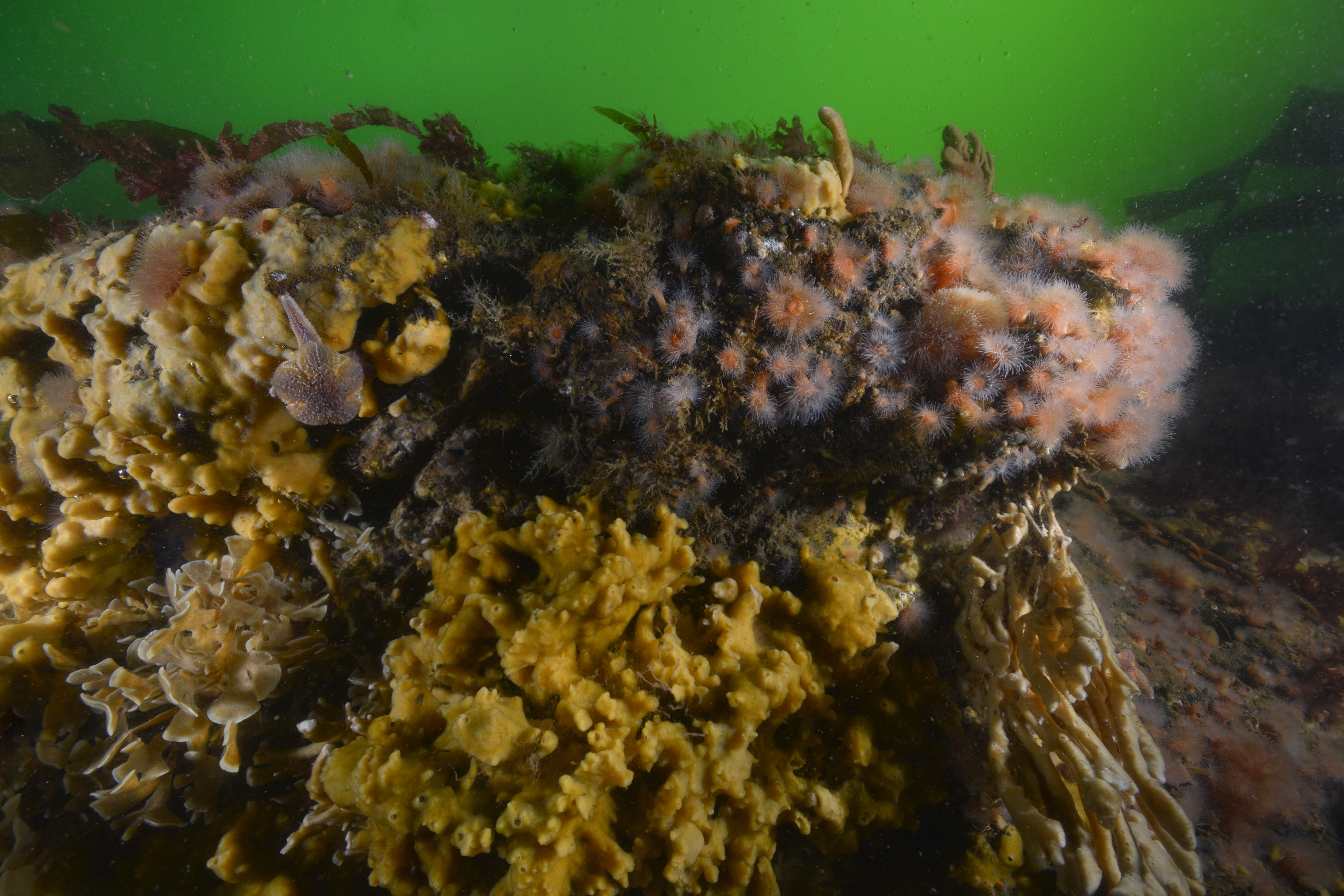

A chain anchored to the bottom made an easy trail to follow out to the wall. Expanses of eelgrass quickly changed to sugarkelp, a brown algae resembling large lasagna noodles. Goldsinny wrasse darted amongst the fronds along with the omnipresent moon jellies. Frequently brushing my face, I was grateful they did not sting! It was an environment unlike anything I had seen before, but huge quantities of sediment made photography an impossibility.

Following the chain to a depth of seven metres, we reached the first level of the wall. Along the top, sugarkelp and Laminaria hyperborea, a leathery seaweed, undulated gently—an indication the current was still slack. Following the chain, we descended to a plateau with a width of two to three metres. Farther down was another wall and another step before it sloped down to 25 to 30m.

As Peter said, the seabed was flat and lifeless at that depth, so we opted to stick with the wall. Descending farther, the environment changed yet again. Sea squirt colonies abounded along with pink oaten pipe hydroid and plumose anemones. The wall itself was not actually rock, but clay. Nevertheless, it was riddled with nooks and crannies, providing hiding places for fish and molluscs. A viviparous eelpout (one of the most unlikely fish names I ever heard) added a splash of red to the yellow of the sponges. Shooting close to the wall with twin strobes really helped minimize backscatter.

Heading back, the current picked up considerably. Struggling with my release valve, I turned it the wrong way, filling my suit with air. Holding the chain at the safety stop, my feet went upwards and the rest of me promptly followed. Fortunately, we were not deep, but I surfaced right into a current, which started whisking me away from the jetty. After a brief bit of panic, I managed to get ashore. Peter volunteered to return to the house to make us some lunch. Reluctant to shed the drysuit, I remained to snooze on the jetty.

Final dive

Weary, yet undeterred, I was eager for another dive. Heading back down, we followed the chain to the wall. The rocks at the base proved to be my favourite part of the dive. Upon closer scrutiny, a myriad of creatures was revealed.

Clusters of blue mussels abounded, as a myriad of crabs scuttled. Red whelks were everywhere; many were encrusted with tiny strawberry anemones. One whelk yielded a real surprise. Hitching a ride was a nudibranch so small, I failed to see it until examining the photo on my laptop. I spotted another eelpout and this one sat still long enough for me to photograph it. Illuminated by my torch, the colours were quite striking, especially in contrast to the wall’s grey tones.

Perched vicariously atop one kelp frond, a tiny spider crab brazenly raised its pinchers in defiance of my close approach. I could just make out a Yarrell’s blenny peering out from a crevice but could not get a photo. Tadpole fish could also be observed along with the occasional lobster.

Then, it got cold. REALLY cold. Turns out we blundered into a serious thermocline. I was so engrossed with my photography that I scarcely paid much attention. Some 15 minutes later, it was a different story. Warmer water beckoned, and we made our way back to the shallows. This time, I was grateful my safety stop did not involve shooting to the surface feet-first. Back on shore, I was elated that everything went perfectly for our final dive. It turned out the water was a brisk 6°C. “If you can handle that, you can dive pretty much anywhere,” said Peter with a grin.

Diverse diving

The entire Little Belt area offers a variety of dive sites. Just before the old bridge on the way to Jutland, a turnoff leads to Kongebrogaarden Marina. Adjacent to the Marsvinet Dykkerklubben (dive club), an underwater trail follows the stone reef into the Little Belt. Ideal for novice divers, the trail extends for 50m, with a maximum depth of 12mm.

Along its length, nine markers provide information about the diversity of life to be observed around the reef. Signs are numbered one through nine, with an arrow pointing to the subsequent marker. Fish species vary depending on the season, with viviparous blenny, topknot, goby, lumpfish and goldsinny wrasse frequently observed. Nudibranchs are especially common during the winter months. Another trail starts near the Café Jazz in Middelfart, continuing along the coast right to the dive club.

For our last night, we headed back into town for another meal at the Café Jazz. Securing a table on the patio, we enjoyed pre-dinner drinks as the setting sun silhouetted the Old Little Belt Bridge and painted the horizon with crimson tones. A harbour porpoise appeared to complete the postcard setting. Heading back to the resort, we made a stop at Middelfart Harbour. Despite the midnight hour, the last vestiges of sunlight peered above the horizon as fishing boats sat motionless on the still water—another postcard view. That’s Denmark for you. ■

New Nordic Cuisine

Edited by G. Symes

The New Nordic Cuisine is a culinary movement that burst onto the global gastronomic scene in the early 2000s. Developed by chefs in Scandinavia, of which Claus Meyer and René Redzepi were the pioneering innovators and founders of the world-renown Noma restaurant in Copenhagen (four-time winner of the “World’s Best Restaurant” title in Restaurant magazine), the idea was to revamp traditional local cuisine by using principles of “purity, simplicity and freshness” as well as emphasise seasonal produce grown or foraged locally, benefitting from the region’s unique climate, water and soil, including traditional local favourites such as Danish new potatoes, strawberries and asparagus.

In addition, the chefs revived and adapted older Scandinavian techniques, such as marinating, smoking and salting, as well as prepared local organic foods such as oats, rapeseed, cheeses and heirloom varieties of apples and pears, using methods that maintained their natural flavours.

Since its inception, the trend has spread and evolved. In 2004, the Nordic Kitchen Manifesto established ten principles based on “purity, season, ethics, health, sustainability and quality,” written by chefs from the Nordic lands of Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland, Iceland, Greenland, Åland and the Faroe Islands.

Today, the aims of the New Nordic movement have been taken up by many chefs and local kitchens around the world—revamping traditional dishes and creating new ones with fresh local, sustainable and traceable ingredients—as well as governments, institutions, agencies, schools, universities, food production and supply chains, guided by the principles of the Manifesto. ■

SOURCES: The Guardian, Nordic Co-operation, Visit Copenhagen, Wikipedia