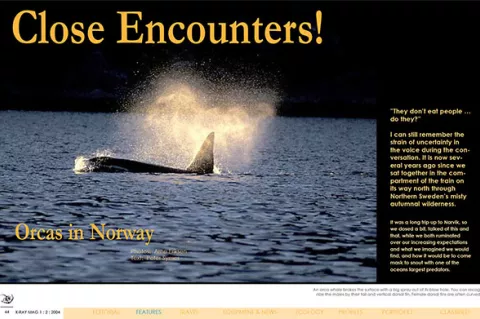

”They don’t eat people … do they?”

I can still remember the strain of uncertainty in the voice during the conversation. It is now several years ago since we sat together in the compartment of the train on its way north through Northern Sweden’s misty autumnal wilderness.

Contributed by

Factfile

ORCA FACTS

SCIENTIFIC NAME: Orcinus orca. The orca is the largest of the dolphin family. It is a member of the toothed whale suborder. It is much smaller than the sperm whale, which is the largest toothed whale. It is commonly called the killer whale, a name which came from early observations of orcas attacking seals and seabirds. In many aboriginal legends, the orca is described as a sea monster. Other names include “blackfish” and “sea wolf.”

DISTRIBUTION: Killer whales are one of the most widely distributed mammals, second only to humans. Orcas are most common in the waters off the Pacific Coast of North America, Antarctica, northern Japan, Iceland and Norway, but can also be found in all the world’s oceans.

DIVERSITY: Orcas have three distinct lifestyles: residents, transients and offshores. Resident whale pods are made up of mother whales and their children and feed on fish. In summer, they regularly inhabit two areas off Vancouver Island. Different resident clans have often been seen travel together. Transient orca pods are smaller and opportunistic in their feeding habits. They eat marine mammals and seabirds. It is thought that transients leave their mother’s group while still young and roam larger sections of the coast from Alaska to California. Less is known about offshore killer whales. It is thought that they travel in large groups of 30 to 60 individuals and seek out schools of fish to eat.

POPULATION: No accurate world population is known for orcas. Some scientists guess there might be hundreds of thousands around the globe. It is estimated that there are 300 residents and 200 transients off the coast of British Columbia.

SIZE: Males grow up to 9.8 metres and a whopping 9,000 to 10,000 kilograms. Females grow up to 8.5 metres in length and weigh 6,500 to 7,000 kilograms. Calves measure 2.3 metres in length at birth and weigh between 130 and 180 kilograms.

REPRODUCTION: Most females give birth for the first time at 14-15 years of age. They have a calve on average once every three years. Orca mothers usually stop giving birth by the time they reach 40 years of age. Captive orcas have a gestation period of about17 months and normally give birth to single offspring.

LONGEVITY: About 50 years for females and 29 years for males on average. Female orcas tend to live longer than males, with an estimated 70 to 80 year maximum age. Males live up to 50 years.

SOURCE:.www.canadiangeographic.ca

It was a long trip up to Narvik, so we dosed a bit, talked of this and that, while we both ruminated over our increasing expectations and what we imagined we would find, and how it would be to come mask to snout with one of the oceans largest predators.

Out there and in free water the “wolfs of the ocean” were waiting for us, those predators known as killer whales.

Narvik in November

What do these three words mean to me? Mostly, I think, as one of the bigger marketing challenges. The town, which is situated some 400 km north of the arctic circle, and whose only real reason for existence has been as the exporting port for the iron ore from the mines at Kiruna in northern Sweden, has all the odds against it in competition with Bountyland.

If it was not for the killer whales I would never have sat my fins here.

We arrived at 10 o’clock in the evening, and it struck me immediately that it was mild and quite light, and completely different from the deeply frozen polar night of my worst imaginings - it was almost like a danish October day. But that, of course, is the reason why the Swedish iron-ore was shipped out from here.

The Gulf stream keeps not only Narvik ice-free the whole year but also all northern Norway and the whole coast right round to Murmansk in Russia. It was because of this that the Allies could supply the Russians the whole year via Murmansk during World War II, under terrible conditions and with enormous costs.

A great sea battle between the Royal Navy and the German forces took place just after the German invasion of Norway 9, April 1940. This battle for control over this strategically important area and Narvik’s harbour has resulted in many exciting war wrecks on the sea bottom around Narvik. But that, as they say, is quite another story.

It is worth remembering though because the wartime wrecks are supposed to be first class. We are however here for another purpose. The boat is waiting for us about three-quarters of an hour’s drive from downtown Narvik, so we choose the easy way and hail a taxi outside the station and speed out of town in a four-wheel-drive Volvo stationcar.

Arrival

A short while later, onboard Strømsholmen’s big and inviting live-aboard boat with a cup of hot coffee, we are positioned just out of an idyllic little fishing village at Tys-fjord, which is a small side fjord to the big Ofot-fjord, which reaches from the wide-open spaces of the Atlantic and in past Narvik. In here, in this little, easily overseen corner on the map, in the back of the beyond, one of the greatest numbers of killer whales known, collect at up to 250 at a time in a small area.

But what is so special about this small spot? Beautiful, it must be said, but above the surface, there is nothing to differentiate it from any other of the probably thousands of fjords and inlets along the Norwegian coast.

The explanation is to be found under the water. Tys-fjord is both deep, cold and stagnant. Therefore large shoals of fat Atlantic herrings come here every Autumn to overwinter. Killer whales and humans have many things in common.

Not only do we humans take a deep breath and come up again for air with a big gasp, have navels and nipples, family life and intelligence, but we also like a good lunch with herring. Each year on precisely the same day, it is said, large herds of killer whales follow after the herrings into Tys-fjord, where they line up for the big feast.

Families

Killer whales form families with strong bonds and hunt in groups. The next morning, after having eaten a long and lazy breakfast, before the sun’s first rose-red rays hit the surface of the water - the sun rises late - we can see out over Tys-fjord where the many killer whales are not spread out over the whole area but are moving to and fro in groups. The time has come, the game can begin.

The game begins

Our skipper manoeuvres the boat out to the middle of the fjord while we look in all directions in order to see everything right from the beginning. It is time, however, to get changed into our warm drysuits. It should perhaps be added here that one doesn’t dive with killer whales but snorkels. There are several good reasons for this.

First and foremost because you can’t follow the killer whales down to the depths - which you couldn’t do anyway because they are much too fast. Also one remains mostly at the surface, as it is here that things mostly happen. Finally, there is the “weighty” reason in that it is not at all amusing to drag a scuba apparatus one doesn’t really need out of the water many times during a day on the water.

RIB-express

The safari works in this fashion. One boards a fast RIB, where it is now essential to be able to spot the direction in which the killer whales are heading, race ahead of them, glide quietly into the water and then let the killer whales come to you. There shouldn’t be too much shouting and splashing as the killer whales are working for their food and they won’t accept too much noise.

Then you just have to lie and wait and stare in the right direction for suddenly to see the whole herd racing towards you through the water. It is a sight not soon forgotten. It is obvious that the killer whales here are wild and that it is their natural behaviour that you are seeing.

They seem to be completely absorbed and focused on their business. For better or for worse they do not appear to be influenced by the presence of humans in their element. The best is that you get a true insight into their behaviour and hunting patterns from a very close distance.

The worse, if you can say that, is that the killer whales don’t make circus acts and that sort of thing; they are busy and don’t have time for messing about. And yet the young ones can be real jokers and full of daring tricks.

There’s one of them that makes the most playful and amusing spiral dance in the water deep beneath me, and which seems to be quite unconcerned regarding the accurately choreographed and precise hunting patterns which the herds otherwise are carrying out.

Naughty children are obviously not just a human phenomenon. And neither are over-protective parents. We spoke on the train coming up about the possibility of them attacking humans (they don’t, there is not one registered occurrence of it happening) but that fear evaporates the moment one comes down into the water with them.

It is like seeing sharks for the first time, one feels much more fascinated than threatened. Most animals that you meet have a behaviour that can be read if you are not too empty-headed and of the type who insists on patting a growling dog showing its bared teeth.

An Idiot

And that is true for killer whales too. Of course one can never know what is really going on in the head of an animal, or that of one’s neighbour for that matter, but the behaviour of killer whales seemed accepting and never threatening. Most of all one feels just a little bit ignored.

We were told that there is just one no-no, and that is: don’t get between a young orca and its mother. That is easily understood. Although apparently not so for an idiotic big city Swede, we were told.

Perhaps it is just one of those wandering anecdotes, told to illustrate a point, but it is not the poorer for that.

The story tells of a killer whale mother that gave an idiot a broken arm and a concussion because he jumped down between her and her young in order to have some fun with the little one. Not surprisingly, he was given such a blow with her tailfin, which he certainly won’t forget in a hurry, that it ripped half of his equipment off of him. But it was his own fault, the idiot.

Curious creatures. The thing about killer whales that makes the biggest impression on me, is not their size and elegance but their “mammalness” and near relationship to us. First and foremost, it is their heavy, deep breathing, from which one can almost feel their body heat, and which reminds one so much of the sounds we ourselves make in the swimming pool. These animals clearly have fins, but they are so obviously not fish.

They have complex behaviour, their playfulness and dolphin-like cavorting, and their ”spy-hopping”, where they pop their heads out of the water in order to see what is going on.

They are clearly curious when they have first satisfied their hunger, and often lie and splash on the surface.

There are many impressions to reflect on when one is back on board and sitting around the dinner table. We are on the water for quite a long stretch, although the sun is only up between 10 o’clock in the morning and 3 o’clock in the afternoon. But that is quite enough because afterwards one is really tired and satiated by the events and experiences of the day.

So it is nice to have some long pleasant evenings in which to talk, to drink a whiskey, or read a thriller. Or, that eternal ritual between divers from around the world, the exchanging of diver gossip and discussion about destinations and equipment.

To say that the days up here resemble each other should not be thought of in a negative way. On the contrary, the regularity and simple way in which one dives, eats, sleeps, eats, dives, in a repeated cycle, is both quietly relaxing and uncomplicated in a peaceful way.

All the worries of the world are so very far away and life so wonderfully simple.

And the days are not all so uniform. Every day we try something new and different apart from the near contact with the killer whales. Actually, it is rather nice to be able to stretch one’s legs on land by taking a hike into the untouched nature. Just around the corner, we find rocks with some very old carvings, perhaps from the Stone Age, where a big whale can be seen carved into the hard granite.

But we also take a couple of really good night dives in the clear water of the lagoon when darkness has set a stop to the killer whales' show of the day, for here it can be done before dinner as the sun goes down so early at this time of the year.

There are, in fact, excellent ordinary diving possibilities here, even though the killer whales do tend to grab all the attention, so one shouldn’t cheat oneself out of putting on a couple of bottles and jumping down and studying the sea bottom.

Carousel

Ah! There’s nothing like a solid breakfast to start the day. And to be well rested after a good night’s sleep is almost guaranteed up here in the long nights.

The sun creeps up over the mountains in the East to clothe the whole landscape in a delicate rose colour while we set out for the middle of the fjord, holding a good cup of steaming coffee. The killer whales seem to be quiet, perhaps they are also B-people, but soon things begin to happen fast.

We are now in our suits, and over to the right, we observe a large flock of screaming gulls over a small area of the sea. It is there, that something is happening. It is there we must go... as fast as possible.

It is a so-called herring carousel, a compact sphere of confused herrings that the killer whales have driven together, in order to strike into the massed food.

It is a fascinating event to observe, that is if one is fast enough. The killer whales hunt in packs, where, like sheepdogs, they drive the herring shoals together into small concentrated spheres. They physically chase them, cutting off their escape routes, and thereafter, they do something very fascinating. They make a fence of air-bubbles.

For some reason or other, the herrings will not swim through this cloud of bubbles, perhaps it frightens them.

The final result of this precisely determined group behaviour is that the killer whales manage to force the herrings together into a compact swirling sphere about 5-10 m in diameter – and keep them there. Thereafter, something else quite as fascinating occurs.

The killer whales take turns at swimming rapidly at the spere and at the last moment turning their tails to give the herring-sphere a really hard swipe with the large fin.

The pressure wave knocks out a large number of the herrings. Now, the buffet is open. One can only guess at how the killer whales have discovered this technique, but one must certainly take off one’s drysuit hat in respect for their intelligence.

And afterwards one can thank them for food since, after such a herring-sphere massacre, there are many herrings remaining on the surface which can just be gathered up. Some of them are totally crushed with eyes popping out of their sockets. What a force there must be in that swipe with the tailfin!

And beneath us, the ocean gleams with thousands of small pinpricks of light. It is all the fish-scales that have been struck off the herrings, and which now fall slowly like fairy-like, sparkling all the way down into the depths.

Recommendation

I could carry on telling small anecdotes about my adventures in Tysfjord. But everything has an end, not only our trip but also this report. Like any restaurant critic, I must also make a summary of my impressions – what was good, what was not, and what types of people are suitable for such a trip... from tekkies to children?

To start with the latter, such a trip requires no other technical abilities than the ability to climb in and out of the boat. Thereafter, one is better off if one has a drysuit. However, the essential thing is to have a genuine interest in natural phenomena to be seen. I would therefore leave at least the babies at home because it would be very difficult to entertain them so many days on the boat.

The good: experiences that remain with you for life.

The bad: a stiff price for the whole project when one includes the cost of getting there. But that’s northern Norway for you. It is far from here and even further from any food producing regions. So, up here vegetables are so expensive that they must nearly be imported in armoured cars with armed escorts, and probably sold in thin slices weighed on letter-scales before being devoutly passed over the counter with tweezers and white gloves.

But that shouldn’t hold one back from making the necessary investment in an experience of a lifetime. ■

Published in

-

X-Ray Mag #2

- Read more about X-Ray Mag #2

- Log in to post comments