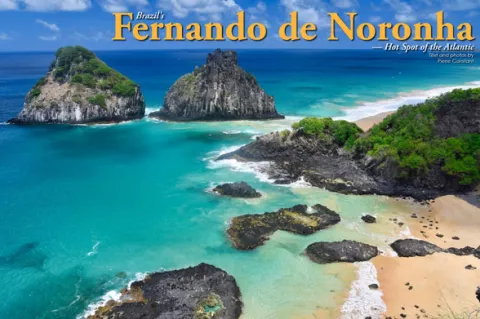

Five hundred and twenty-five kilometres from Recife on the northeastern coast of South America (or 350km from Natal as the crow flies), the minuscule specks of land of Fernando de Noronha are to Brazil what the Galapagos Islands are to Ecuador—but on the other side of the continent. In a way, the two archipelagoes are very similar, both of them are volcanic hot spots born out of fracture zones in the ocean, slightly south of the Equator and a prolific refuge for seabirds.

Contributed by

Laying 3°50’25” S and 32°24’38” W, the 21 islands that compose Fernando de Noronha’s archipelago are much older though, with an estimated age of 30 million years. The hot spot is located on the South American Plate, which moves west-south-west at a rate of 45mm per year and in subduction under South America. Judging by the effect of the West Africa mantle plume, it is responsible for a series of volcanoes that extend west and away from Noronha, including the Rocas Atoll.

History

As the story goes, the archipelago was discovered in 1503 by the Portuguese expedition of Gonçalo Coelho, financed by Fernão de Noronha. It was credited to Amerigo Vespucci though, an Italian member of the expedition, who made the first description of the islands. The French Capuchin monk Claude d’Abbeville visited in 1612 on his way to Brazil where a colony was to be founded. Abandoned, it was later occupied by the Dutch from 1629 to 1635, then fell under the French from 1705 to 1737.

It was finally taken over by the Portuguese in 1737. Consequently, several fortifications were built, including the fortress of Nossa Senhora dos Remédios. Fernando de Noronha would become a notorious prison for political prisoners.

Scientific expeditions such as Charles Darwin’s on HMS Beagle, visited in 1832—before he landed in Galapagos three years later. The early 20th century saw Italian and French settlements for commercial purposes and the laying of submarine cables.

Commercial flights of Aéropostale linked South America to Europe and Africa, with aviators Mermoz and St-Exupéry’s historic runs. During WWII, Noronha became a US Air Force base and a strategic spot on the African war front. On continuation, the archipelago was administered by the Brazilian military from 1942 to 1988, when the islands were declared a Marine National Park. Tourism is nowadays the blood of the economy; Noronha has turned into a dream holiday island for wealthy Brazilians.

Fernando de Noronha became listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 2001. It is now legally protected and managed by the Chico Mendes Institute for Biodiversity Conservation (ICMBio), an autonomous federal body attached to the Department of Environment. Also, part of the Master Plan, Atol das Rocas is administered separately as a biological reserve since 1979 and prohibited to visitors.

The management of Fernando de Noronha involves tourism, research, environmental education, protection and monitoring of biodiversity. A sustainable development plan was put in place for the Parque Nacional Marinho, with the help of the local population, in terms of ecotourism. Touristic infrastructure is strictly controlled, as well as tourism sites.

Getting there

Operated by GOL, the flight from Recife takes only one hour, but there is a one-hour time difference from the mainland. Upon arrival, one is expected to pay the TPA (Permanency Tax), which is BRL 76 per night and increases the longer you stay on the island. You are also asked for the Covid-19 negative PCR test, failing which you are subject to quarantine straightaway. It is also compulsory to approach the Fernando de Noronha Marine National Park office to pay for the entrance fee of BRL 222 (foreigners), valid for ten days only, which you need to show when diving or visiting the national park sites.

Lodging and sites

Most of the lodging is done in pousadas, a version of a guesthouse with variable prices. Life and food are expensive on the island. Diving is obviously one of the most popular activities. There are three dive centres operating out of Porto, on the northeastern coast, with dive shops located in Vila dos Remedios—the colonial Portuguese town, with historic buildings such as the Palácio de São Miguel and the church of Nossa Senhora dos Remedios. The imposing Fort of Nossa Senhora dos Remedios, on a bluff overlooking town, offer great views of Porto, Praia do Meio (Middle Beach) and the iconic thumb-shaped rock of Pico de Meio, a famous attraction at sunset.

Conditions

The islands are exposed to the South Equatorial Current flowing from east to west, as well as to the southeastern trade winds. The “Inner Sea” on the northern coast has calm waters between April and November but experiences waves between December and March, when the northeastern trade winds become preponderant. Being exposed to the southeastern trade winds, the “Outer Sea” on the southern coast is usually rough but has clearer visibility.

Dive conditions are therefore influenced by the period of the year, and dive operations choose the sites accordingly. Water temperature is 28°C all year round, with a visibility ranging from 25m to 40m. With its 25 dive sites, Noronha is considered to have the best diving in Brazil.

Underwater landscape

Being essentially volcanic basalts in black, the underwater landscape is rather dull, with boulders, ridges, and sometimes canyons, swim-throughs and caves. In places of current, such as channels, sponges cover rocks, which turn very colourful in bright red tones. Otherwise, beds of green algae and sea grapes are the norm.

Diving

Divers are picked up at their pousada by the dive truck, every morning at 7:15 a.m. Upon boarding the catamaran, face masks are compulsory. The dive briefing given by the guides covers facilities on board and the dive sites. Some of them do speak English or Spanish, although Brazilian is the norm. Dive sites are anything from 10 or 15 minutes to a maximum of 30 minutes away. During my stay in December, most of the diving was done in the Inner Sea, i.e. on the northern coast between the eastern and western points of Noronha.

Cordilhieras. Cordilhieras, near the northeastern tip, is a submerged ridge with lots of algae. A common sight there is a small school of yellowstripe grunts (Haemulon chrysargyreum). Female Brazilian reef parrotfish (Sparisoma amplum) are green on the back and red on the belly, and adult males turn light blue with a red crescent on the tail. Bermuda sea chubs (Kyphosus sectatrix), which are grey in colour, move in small schools, as do the black margate fish (Anisotremus surinamensis), which are large-bodied and silver, with a steeply angled head and a black patch behind the gills. I came across a hawksbill sea turtle (Eretmochelys imbricata), which was absolutely tame and oblivious of us divers. The blue tang (Acanthurus coeruleus) is one of the rare species of surgeonfish around.

Ilha do Meio. Ilha do Meio (Middle Island) lies between Ilha Rata and Porto. The idea is to explore essentially caves and swim-throughs in shallow water, where you sneak in and out behind the dive guide, while the official underwater photographer of All Angle Images waits for you on the other side. Photos of divers will be shown at the dive shop in the evening, and you can make your choice for R$30 (5 Euros) a piece. Wannabe Brazilian divers are naturally delighted by such memories.

The caves are alive with copper-toned glassy sweepers (Pempheris schomburgki), small coney groupers with blue spots and yellow bellies (Cephalopholis fulva), pairs of French angelfish (Pomacanthus paru) and blue tangs. As you emerge from the dive, you may find black noddies (Anous minutus) and tropicbirds (Phaeton lepturus ascencionis) happily flying about.

Caverna da Sapata. At the western tip of the island, Ponta da Sapata is a nesting site for red-footed boobies (Sula sula). An underwater arch with a sandy bottom is a refuge for southern stingrays (Dasyatis americana), with pepper-coloured spikes on the back. Undisturbed by divers, they keep a Zen attitude. “Some turtles get lost in remote corners of the cave and end up as skeletons…”, confirmed our divemaster Julio, who was happy to pose, all smiles, next to a skull. Good visibility favours great pictures. A miniwall on the outside of the arch revealed three scrawled filefish (Aluterus scriptus) and an orange-coloured whitespotted filefish (Cantherhines macrocerus).

Cagarras. Cagarras, on the eastern side of Noronha, west of Rat Island, is a nesting site for masked boobies (Sula dactylatra). A deeper dive in the 32m zone, it is a spot for Cape Verde spiny lobsters (Panulirus charlestoni), black jacks (Caranx lugubris), French angelfish and the conspicuous Brazilian parrotfish.

Buraco das Cabras. Buraco das Cabras, at 20m in depth, is more productive, photographically speaking. A wandering nurse shark (Ginglymostoma cirratum) created a stir, eventually approaching me without fear. Big stingrays covered in sand watched divers go by with a serious look. Frantic displays by Brazilian “yuppie” divers made a show of exuberance with open arms, behind a turtle and in front of the official photographer. I had to wait patiently for my turn to approach the creature grazing between the rocks. An ocean triggerfish (Canthidermis sufflamen) sailed by, and Bermuda sea chubs burst in small clouds. At the end of the dive inside the channel, between Ilha Rata and Ilha do Meio, a rather large, old Portuguese anchor, encrusted in red sponge, caught our attention. Drifting with the current, I flew over a lovely peacock flounder (Bothus lunatus) carpeting a rounded rock.

Cabritos. Cabritos, on the northeastern tip, begins in Mar de Fora’s (Outer Sea) clear waters entering the channel. It is a colourful shallow site, with lots of mushroom-shaped rocks covered with sponges. Black jacks and a school of doctorfish (Acanthurus chirurgus), horse-eye jacks (Caranx latus) with forked yellow tails and yellow goatfish (Mulloidichthys martinicus) complete the show. A second old anchor, even bigger than the first, left my mouth agape.

Cabeço da Sapata. My wish for the last day of diving was granted by dive guides Leo and Julio. On the western tip of the island, this offshore underwater pinnacle is usually subject to strong currents and water movements, but we experienced just a gentle swell. A large nurse shark passed by like a shadow over the white sandy bottom. A little school of horse-eye jacks swirled by. Dog snappers (Lutjanus jocu), which were silver in colour with bars on the back, drifted like peaceful Zeppelins. Clouds of yellow-edge chromis (Chromis multilineata) swayed with the current over the pinnacle and schools of black triggerfish (Melichthys niger) hovered in the blue.

Trinta Reis. Trinta Reis, in the Mar de Fora, is located in the middle of the southern coast, in-between emerging rock islets. The ocean was choppy as expected, but underwater it was all calm and serene. The white sandy bottom is carved by ripple marks over a vast expanse, which provide the best photographic effect. We cruised into a swim-through, entering a canyon with southern stingrays and black jacks. Exiting out of it, I witnessed a Caribbean reef shark (Carcharhinus perezi) wandering majestically over a vast expanse of white sand.

It had an atmospheric environment, with a lot of light, which made one forget that once upon a time Fernando de Noronha was a place of extensive artisanal shark fishing, between 1992 and 1998. Species targeted included the dusky shark (Carcharhinus obscurus), Caribbean reef shark, silky shark (Carcharhinus falciformis), lemon shark (Negaprion brevirostris), nurse shark, tiger shark and hammerhead shark—a sad history for these islands.

Wildlife

Wildlife on oceanic islands is extremely limited; mammals are virtually nonexistent in Noronha, with the exception of rats and the mocó. This chestnut-coloured rodent, which resembles a small capivara, was introduced by the early settlers and meant for food. The black and white tegu, a lizard (Tupinambis merianae) found primarily in the forest, was introduced from Brazil’s northeast in the 1950s to take care of rats. It is about 40cm long with a pink forked tongue, like a monitor lizard. Unfortunately, it also attacks local birds and has proven to be an unwanted predator on the island.

When Charles Darwin went ashore on 20 February 1832 (three years before he visited Galapagos), he marvelled at the lush tropical forest with magnolias, laurel trees adorned with delicate flowers, and trees bearing fruits. Sadly, these original forests no longer exist, since Noronha became a penal colony. By the end of the 19th century, the island was almost completely deforested. The formal prison island lasted until 1957. A slow recovery began in 1988, when Fernando de Noronha became a Marine National Park.

Seabirds seem to be totally at home on the islands. Colonies of red-footed boobies, in both the coffee-coloured and the morpho-blanco varieties, are found nesting in trees on the extreme end points of Noronha. Brown boobies (Sula leucogaster) are seen fishing and diving along the beaches of the northern coast. Masked boobies (Sula dactylatra), which are white in colour with a yellow bill, roam the southern coast exposed to the trade winds. Other common seabirds include the black noddy, white tern (Gygis alba) and tropicbird, which has a yellow beak and long yellow twin-feathered tail.

Conservation

Conservation projects are managed by the ICMBio. Besides the biological reserve of Atol das Rocas (137km west of Noronha), which was created in 1979 and is off limits to visitors, two main projects come into view. The Tamar Project for the conservation of marine turtles deals with five species known to visit the islands: the green (Chelonia mydas), hawksbill, loggerhead (Caretta caretta), olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) and leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) sea turtles. However, only the first two are commonly seen in the waters of Noronha.

The other project concerns the spinner dolphin (Stenella longirostris), which has a resident population in Baia dos Golfinhos, a secluded bay to the northwest of the island. A viewpoint is accessible to visitors who come early in the morning to watch the dolphins porpoising and playing in the bay. Scheduled guided walks are offered by the park office.

Topside excursions

A number of trilhas (trails) are available for the independent visitor to the Marine National Park. Some of them cannot be undertaken freely and require advance booking, since they are led at specific times by a licenced guide of ICMBio. Most of these trails lead to beaches or viewpoints of interest and are anything from 15 minutes to up to three hours long.

A number of agencies also offer private tours with their own transportation, or even cruises for snorkelling or watching dolphins. Well-to-do Brazilians often choose to hire flashy colourful “buggies” for the day, sharing them with friends, which gives them autonomy and a happy-go-lucky feeling, at a hefty cost though of R$300 to 350 per day (50 to 60 Euros).

However, for the independent-minded traveller on a budget, it is possible to catch the free Coletivo (omnibus), which crosses the island from northeast (Porto) to southwest (Sueste) along BR-363. It runs back and forth all day long, providing access to the trail heads of all the trails and exotic beaches. Fernando de Noronha is truly a Brazilian experience, where the foreigner is most welcome, but certainly an oddity!

Towards the end of my stay, I passed by a house with a colourful signboard on the entrance gate. “Sorria, voce esta na Paraiso,” it said, which means: “Smile, you are in paradise.”

They call it paradise for sure, but paradise is indeed in the eye of the beholder. ■

With a background in biology and geology, French author, cave diver, naturalist guide and tour operator Pierre Constant is a widely published photojournalist and underwater photographer. For more information, please visit: calaolifestyle.com.